Reviews (863)

Bald Mountain (2013)

The run-of-the-mill story about the rise and fall into crime gets a refreshing enhancement in Bald Mountain by setting it in the impressive setting of an enormous open-pit gold mine in Brazil called Serra Pelada (the titular Bald Mountain). In this real location, a microcosm of both organised and completely freelance crime developed during the six years that the mine was in operation, starting in 1980, and the depiction of that world is the main attraction of this skilfully made film. The film’s narrative focuses on two friends who start out here among the tens of thousands of ordinary miners swarming like ants in the iconic shots of the open-pit mine, but gradually work their way up, becoming tycoons and then later falling apart under the influence of gold fever. The film properly balances the formulaic story with the presentation of all possible aspects of its setting. The filmmakers succeeded in using a combination of period shots, digital effects and artfully filmed scenes to evoke the atmosphere of a giant human anthill as a place where wealth comes just as quickly as death.

Zip & Zap and the Marble Gang (2013)

Based on the poster, Zip & Zap and the Marble Gang looks like a Spanish knock-off of Harry Potter, but it turns out to be an excellent film for children that captivates with its fantasy world mixing hyper-stylised sets and costumes with adventure in the style of Amblin’s 1980s classics. The film is very loosely based on José Escobar’s comic books, but instead of their anarchistic humour and phantasmagorical plots (vaguely speaking, something like a children’s version of the Clever & Smart comic books), the filmmakers came up with a surprisingly orderly narrative that places characters similar to those from the original comic books in a classic adventure story full of big secrets, hidden treasures, secret passages and all kinds of fantastical mechanical devices. The central motif of the film becomes a celebration of play as opposed to the terror of education aimed at instilling obedience and dolorous study, which is conveyed by means of a totalitarian boarding school where children are supposed to be divested of their imaginations, but which turns out to be a maze interlaced with secret passageways providing a magnificent adventure.

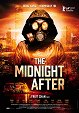

The Midnight After (2014)

This bizarre adaptation of a web-novel about a diverse group of people who are the only ones remaining in Hong Kong after a mysterious event reflects on the socio-political phenomena of Hong Kong and its population in recent years through the use of fantastically exaggerated passages, the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear power-plant disaster, the upcoming Hong Kong Legislative Council election, which highlights China’s influence on the self-governing region, and of course the future deadline of 2046. The premise involving the disappearance of all of Hong Kong’s people and the simultaneously disturbing and fascinating images of empty streets, which we are otherwise used to seeing full of people, refer to the concept of the “culture of disappearance” – the intensive search for Hong Kong’s identity and for the past and contemporary culture in a period when Hong Kong is faced with the threat of political and cultural assimilation into China. The result is a metaphor rich in meaning that resonates powerfully with the domestic audience, but which remains an impenetrable wall of strangeness for foreign viewers who lack the background necessary to decipher it.

Gravity (2013)

Gravity is a gripping film in which the levels of revolutionary technological advancement, spectacular blockbuster, physically intense suspense and personal drama are in perfect balance and symbiotically form a flawless spectacle. The film is captivating in the way that it conveys the wonder and terror of space, but it also tells a purely human story of inner rebirth that takes place through facing one’s own pain and transforming agonising loss into empowering melancholic mourning. Among other things, reflecting on the film raises the question of whether it is appropriate to describe it as science fiction. It is true that, unlike works typically associated with the sci-fi genre, Gravity does not take place in the future or on other planets, nor does it contain any elements of fantasy. However, in terms of its motifs, it simply cannot be classified otherwise. It has very little in common with futuristic equivalents of fairy tales, westerns and romantic adventures like Star Wars and Star Trek, but such stories comprise only one segment of science fiction. Conversely, the latter contains works that place emphasis on relating humanity to space, which relativises traditional values and concepts of human existence. The highlighting of these motifs and the bold thematisation of the spectacular nature of space, as well as the screenwriter’s creative license in the approach to the scientific and realistic aspects, sets Gravity apart from films relating to real space travel, such as Apollo 13, where space is essentially used as a mere backdrop. In Gravity, space and the action set in it comprise a metaphor for the inner drama of the film’s protagonist, which in turn reciprocally forms the dramatic framework for the depicted spectacle.

Barbara Broadcast (1977)

Radley Metzger himself says that Barbara Broadcast is a creative lark after the spectacular The Opening of Misty Beethoven, but it can also be described as a spin-off, or simply a different story from the same world (an idea that is bolstered by the fact that the final bondage scene, presented as a memory, was created for and eventually left out of the previous film). The narrative again takes us into the world of celebrities and the upper class composed of renowned businesses and luxury offices, though we don’t get a realistic or exploitatively prejudiced view of the life of the upper crust, but a satirically twisted version of it. Instead of real asexuality and sterile superficiality, we are invited into a world where sex is a ubiquitous, everyday thing. Thanks not only to the bold thematisation of New York and its high society, Barbara Broadcast seems today like a sexually explicit paraphrase of Sex and the City, except here the suspense prevalent force is a consistently applied sexual revolution – sex is a matter of asking for it or an opportunity presenting itself, so the characters do not have to deal with any frustration or romantic relationships. Just as we could marvel at the humorous airline sex scenes in The Opening of Misty Beethoven, this time we are in a luxury restaurant where the menu includes not only food and drinks, but also the bodies of waitresses and waiters, or a combination of both, and where a passionate threesome on the stairs in the bar is as common a sight as two guys arm wrestling at a nearby table. This immediacy also brings absolute freedom of pleasure in terms of individual practices, so things that are now confined to specialised genres such as pissing, bondage and anal are not surprising here (the film was made many years before anal sex became a prevalent practice in mainstream American porn). Everything that happens in the film is shrouded in a dreamlike atmosphere of discontinuity and episodicity, which is heralded by the opening title announcing that the events in this film are based on real fantasies. However, at least the first half of the film has the same drawback as The Opening of Misty Beethoven, where sex acts inevitably lose their erotic appeal due to the fact that they have become commonplace. The change of mood in the second half is thus all the more welcome, as the sequences get a more sensual and seductive form. The highlight of the film is the unforgettably raunchy kitchen sequence, which is one of the best porn sequences in history thanks to its hot atmosphere, dynamics of seduction and blissfulness.

Dr. Akagi (1998)

Imamura always approached his characters as representatives of the human race with genuine fascination, but whereas in the 1960s his films were characterised by a rather anthropological coldness and a satirical, and thus essentially evaluative, point of view, the films from the last third of his career radiate greater enthusiasm for and sometimes even celebration of the everyday and corporeal as the basis of all human actions. We can see this slight change not only as the maturation of his creative approach, which tellingly came after the director’s documentary period, when he got a better insight into the realistic archetypes for the heroes and heroines of his fictional films, but also as an expression of defiance against the increasing aloofness and artificiality of (not only Japanese) society in the last decades of the twentieth century. Imamura’s jovial odes to human nature, such as Zegen, Dr. Akagi and Warm Water Under a Red Bridge, are peculiarly and unfairly overshadowed by his seemingly more serious films such as The Ballad of Narayama and Black Rain. However, his films like Dr. Akagi are the essence of Imamura’s approach to the human race and its toil set against the backdrop of major historical events. The titular Dr. Akagi is the quintessential Imamura protagonist – a character of the people who has been forgotten by history, but whose story can tell us much more about the people and, in particular, the Second World War than any heroic epic can. The ridiculous, eager little man, obsessed with the idea of hepatitis infection and diagnosing all of his patients with hepatitis as a matter of principle, is simultaneously a fool, a hero and a subversive saviour when he administers glucose and prescribes bed rest and a hearty diet to everyone around him at the end of the war, a time of tense uneasiness, dwindling food rations and feverish, unrealistic efforts to reverse the course of the war. At the same time, his story is also about the bitter conflict between a man with the ambition to help and the machinery of history represented by a tenaciously stupid and limited military apparatus (in this respect, one of the highlights of the film is the moment when the doctor uncovers the cause of the hepatitis epidemic). Imamura populates the film with a fascinating gallery of supporting characters, all of whom not only aid the depiction of the absurdity of the war situation, but also express the amazing togetherness of people at a time when the absurd civilisational concepts of hierarchy, morality, ethics and good reputation have simply ceased to apply. Besides the profligate Buddhist monk and the brilliant morphine-addicted surgeon, a stand-out character is the girl Sonoko, whom the doctor hires as a nurse so that she will stop selling herself, but she fails to follow through with this because of her ridiculous circumstances and is even discouraged from doing so by her younger siblings. Together with Zegen, Dr. Akagi is a wonderfully absurd depiction of the Second World War in the Japanese context that will leave viewers with a bittersweet feeling of catharsis over the essence, futility and, mainly, foolishness of human drudgery. Paradoxically, it can even be said that in these films Imamura actually achieved that classic aesthetic ideal of mono no aware (the pathos of fleetingness in relation to human actions), so greatly promoted by Yasujiro Ozu, with whom Imamura began his career as an assistant director, though even before making his own directorial debut, he had developed an aversion to the revered master and his value system (after leaving the Shochiku Studio, Imamura found an ideal mentor in Yuzo Kawaima, a hedonistic admirer of human baseness). Whereas Ozu melancholically lulls viewers with odes to the middle class, Imamura opens up for them a world free of bourgeois refinement and instead empathetically celebrates corporeality and instinct.

Urban Fighter (2012)

The scariest thing about this work by exceedingly ambitious practitioners of the martial arts is the fact that they clearly didn’t intend it to be camp, but a serious drama. Street Gangs: Show No Mercy thus remains cautionary proof that formulas have a reason to exist in fighting movies and how important dramatic build-up is in fights, not to mention the necessity of acting ability and good sense on the part of the filmmakers.

Sex World (1978)

SexWorld fully deserves its status as one of the best and most renowned porn flicks not only of the Golden Age of American production. As the promotional slogan on the poster admits, the film’s premise is loosely inspired by the high-concept hit Westworld (1973) and its sequel Futureworld (1976). Except this time, instead of an amusement park populated by robots and offering a flawless illusion of the Wild West, we have a sort of spa to which sexually frustrated people go for the promise of the opportunity to live out their fantasies. The concept is perfect for a porn film, as it makes it possible to freely link together a wide variety of sex scenes, but it isn’t used only as a simple donkey bridge. The constituent episodes are built on empathetic depictions of the broadest variety of sexual preferences and sexuality thus becomes a means of profiling individual characters. The world in which any fantasy can be made real thus becomes a mirror of the characters’ personalities as well as a figurative illustration of the general conflicts and frustrations in human society and romantic relationships. Though the film has no shortage of exaggeration and humour, each segment is rendered with maximum empathy. Instead of the matter-of-factness and efficiency that inundated porn with the advent of the video market, SexWorld is marked by the ambition to approach sex in an erotic way while placing emphasis on the impressive expression of the characters’ desire and pleasure. Thanks also to the great casting of both established porn stars and newcomers (Kay Parker, Annette Haven, Desiree West, Sharon Thorpe, Lesllie Bovee, Jack Wright, John Leslie) who possess charisma and acting ability in addition to their physical attributes, the characters have nothing in common with the one-dimensional and characterless figures that we associate with mainstream porn today. By contrast, the men and women in SexWorld have an attractiveness that goes beyond the physical.

West Side (2000)

The annually updated official ranking of the best porn movies of all time compiled by AVN magazine doesn’t merely list the timelessly best films in terms of the imaginativeness of the given concept, acting quality or the ambitions of the filmmakers, but also serves rather as a representative overview of the decades and trends within mainstream porn. Therefore, alongside well-known classics and original films from the Golden Age, we can find titles that do not in any way measure up to them and are rather unintentionally amusing. This is the case with the overrated West Side, in which the ambition to make an interracial porn flick along the lines of Romeo and Juliet conceals a generic product from the turn of the millennium. Here we see the characteristic elements of the period, such as the bland visual aspect of early digital cameras, insipid plastic pseudo-beauties, forced spectacular sex, a focus on performance and absurd machismo. All of these elements could be taken as secondary manifestations of the period when the film was made, but there is simply no excuse for the entirely slapdash and embarrassingly formulaic rendering of the plot passages. The opening sequence involving a would-be bombastic shootout at a petrol station, the stupidity of which evokes the legendary petrol-station scene in Zoolander, foreshadows the imbecility of other passages showing both sides of the feuding “families” of white mobsters and black gangsters. In such a context and performed by mostly tragically bad actors, the direct allusions to Romeo and Juliet, including the absurd balcony sequence, come across not only as funny, but also as absolutely desperate.

Giovanni's Island (2014)

This absolutely disarming anime film lays out before the viewer a moving story that begins with the end of the war and the Russian occupation of a small island formerly belonging to Japan. The whole situation is conceived from the perspective of two young brothers. The boys establish a friendship with the daughter of a Russian officer, but they perceive the darker side of the occupation through their father, who supplies the island’s inhabitants with food from the hidden reserves left behind by conscripted Japanese soldiers, and their uncle, who smuggles scarce goods to the island. The film is also a great tribute to Kenji Miyazawa’s classic children’s book Night on the Galactic Railroad, which both brothers love and which is the only firm fixture in their lives. The film shows the children’s imagination stimulated by the book not in a kitschy way, but as an essential part of childhood that enables us to accept a difficult reality.