Reviews (840)

Chasing Fifty (2015)

Thank God for the youngbloods of Czech cinema, who are not afraid to go beyond the boundaries of good taste, to break with narrative conventions and to step out of restrictive genre pigeonholes. Kotek’s way of telling a story does not in any way conceal the fact that Chasing Fifty is based on a stage play of the same name. He goes against the trend of increasingly frenetic entertainment, instead basing most of the film on a conversation between three men in a single mountain cottage. We learn everything we need to know from the words that we hear. Vilma Cibulková’s parallel trip to the aforementioned cottage ingeniously raises the false expectation that the two storylines will be more tightly intertwined and continuously complement each other. Instead, they come together only at the end, so that the individual stages of the woman’s journey end up being only distracting red herrings. Similarly, the flashbacks – in which there are very unconventional (almost avant-garde) temporal relationships – do not coalesce into a coherent whole, but serve mainly as a redundant illustration of what we hear. This is an inspiring example of hypermediation, in which the old medium does not merge with the new, but comes to the fore (theatrical rigidity, a transparent attempt to keep the characters in an enclosed space for as long as possible, the doubling of a single message by depicting it in both words and images). The film’s creators take an obliging approach to the scattered attention of television viewers by giving preference to a sitcom-style plot composed of loosely connected gags over a more cohesive causal interconnectedness. Thanks to its disregard for narrative logic and rejection of any consistency in the characters’ actions, the film is enjoyably unpredictable. Another unexpected aspect is the abrupt changes in tone along the lines of the “anything goes” approach of modern eclectic artists. The filmmakers are not afraid to cross the high with the low, laughter with tears, blood with semen. Humorous scenes reminiscent of animated slapstick – including the Mickey Mousing that another progressive Czech filmmaker, Zdeněk Troška, likes to use – are juxtaposed with, for example, a scene in which one of the characters has his skull punctured and his leg stabbed (so badly that he loses it). Kotek and Koleček also refused to give in to the unwritten demand for a more sensitive portrayal of a bygone era that would not turn normalisation into an ostalgic open-air museum of crazy hairstyles, knitted sweaters, tight trousers and Polish condom vending machines. For them, the Communist era is only about the surface, because dealing with politics in the post-modern era without grand narratives is passé anyway. The playful caricature of normalisation corresponds to the film’s concept of itself as a self-assured generational manifesto that ridicules the past regime and adults – the older characters are either hysterical and clumsy (Kateřina), pedantic, heartless and inconsiderate (Pavko) or an outright psychopath who “reads” animal entrails instead of newspapers (Kuna). Both the younger and older characters are defined by a single characteristic, in that they are one-dimensional types, which fits well with the exaggeratedly comedic tone of some scenes and contrasts nicely with the attempt at nostalgically touching tragedy found in other scenes. However, I consider the film’s consistent antifeminism to be its most daring departure from the dominant current of contemporary genre cinema. Chasing Fifty is subversive in its conservative chauvinism, its guyish “highlander” humour about women, homosexuals (who drink cranberry juice) and the disabled. There is not a single positive, let alone active female character who acts of her own accord (rather than out of a desire to please men). Rather, the women in the film are lustful sexualised objects who can be happy that someone wants to have sex with them (and thus drive their sadness out of their bodies). In the deluge of films celebrating the awakening of female power, this is truly very refreshing. I look forward to seeing what the promising screenwriter, who has previously shown an extraordinary understanding of the female spirit (Icing), will surprise us with next. I am equally curious as to how Kotek will further develop the humorous motifs from the film that made him an idle to teenage girls (in comparison with Snowboarders, Chasing Fifty is different in that, for example, sex sometimes leads to the conception of a child, so the characters don’t just figure out who slept with whom, but also who is whose son/father/brother).

Chevalier (2015)

Shot in all seriousness (and cold colours), Chevalier is an absurd comedy whose numerous symmetrical compositions transform the characters into players on a notional sports field. The characters themselves determine the “sports” disciplines and the rules thereof. Like all social creatures, they infer the acceptability of their behaviour from other people. Social rules and rituals are both amplified by the laboratory-like closed environment and stripped to the marrow as something that is often completely absurd, defying “common sense”, which all of us like to reference when we need to justify some of our decisions. At the same time, absurd is becoming increasingly natural as everyone around accepts it based on an unwritten agreement. For them, competition is the dominant means of relating to the world. It is not enough for them to be who they are, as they need to prove that they are better even though – for the outside observer, which we become thanks to the distanced camera – that doesn’t amount to anything. (At the same time, engaging from a distance elicits uncertainty as to whether or not someone is watching and evaluating what they see.) ___ Their homoerotically tinged focus on physical performance, appearance, strength and condition is not motivated by the game. Emphasis on physicality is evident from the opening shots, when the men touch each other while changing clothes, working out or looking in the mirror (thanks to which we will later be able to watch both the evaluator and the object of evaluation). Perhaps due to their uncertainty with respect to their sexual identity, the risk that they may start to in any way enjoy the company of other men, they transform their stay together into the pleasure of open competition. The go all out in everything they do because of the points that they can score. Though the male-bonding theme is not crucial for the film, I enjoyed watching it as a critique of male obsession with measuring (and re-measuring) oneself against others. “Friendship” built on competition. Legitimising meaningless activities by turning them into a game. Construction of phallic shelving units for CDs. ___ I understand Chevalier, at its core, as a satirical story about man’s confrontation with himself as a member of a society based increasingly on market exchange. Anything we do has a certain value. We ourselves have a certain value (human capital) and we strive to constantly increase it in our own interest, to make a good impression and to be popular (perhaps even by willingly sharing information about our private lives). The pathological culture of “likes”, pervasive opportunism, total instrumentalisation of relationships. To the extreme. 80%

Christmas with Elizabeth (1968)

My Sweet Little Village without Menzel’s refined touch. Both when he is at home in his dingy studio apartment and when he is at work, the solitary truck driver played by Vlado Müller sticks to his routines, which long sections of the plot are dedicated to depicting. In her only film role, Pavla Kárníková portrays his unpunctual assistant, who conversely has no respect for order or authority. They can’t stand each other at first. They’re sure about that in advance. He sees her as a “whore” and a “bitch”, while for her, he is a grumpy “old man”. Through their dark past, however, they gradually find common ground and come to realise that it is possible to step out of the roles to which they have become accustomed or that society has assigned to them. In his case, it is the role of a curmudgeonly bachelor who holds others at arm’s length, whereas her role is that of a troubled “slut”. Unable to express their feelings in a healthy way, the two outsiders come together during Advent, and the undecorated tree and lonely Christmas dinner add a sense of melancholy to the raw, authentically gritty story. In the context of the collaborative works of Kachyňa and Procházka, Christmas with Elizabeth fits in with Hope, which took a similarly humane approach to depicting the relationship between a prostitute and an alcoholic, other social outcasts who in the 1950s were condemned to the roles of criminals unworthy of any understanding. 75%

Christopher Robin (2018)

Even though Eeyore was my favourite nihilist before Bernard Black, I never became a member of the Winnie the Pooh fan club. Therefore, I was curious about Christopher Robin, a sort of sequel to the previous animated films, mainly because of the director and one of the screenwriters (mumblecore veteran Alex Ross Perry, whose influence is apparent especially in Eeyore’s heavy existential lines). ___ A total of five screenwriters alternated in and out of the project during its development, which may be the reason that the result seems so clumsy and disorderly, and that the film never gets a firm footing and does not work as family viewing, as Disney apparently intended. The story, which is about an overworked man focused on profit and performance who evidently suffers from PTSD due to the war and neglects his wife and daughter until he rediscovers his inner child thanks to a talking teddy bear (and a pig and tiger and donkey) or, rather, until he stops denying his existence and hiding the talking stuff animals from others, is mainly inconsistent. At times, it is basically a serious drama about an empty, bland existence, and at other times exaggerated slapstick (especially the scene with Gatiss, who is reminiscent of villainous capitalists from classic Hollywood movies). The style is predominantly very naturalistic, with desaturated colours, a hand-held camera lying alongside soldiers in the foxholes of World War II, and animated characters that look like actual soiled stuffed animals from the protagonist’s childhood. At still other times, however, its playfulness lends the film a touch of liberating magical realism á la Paddington (chasing Pooh around the station, the final pursuit). The rhythm of the narrative is similarly unbalanced, as it lacks momentum and a clear aim. The film is unable to decide whether Christopher’s priority should be his family life, his career or his relationship with Pooh, as if completely forgetting about one of these motifs for a moment and blindly following another instead of somehow cleverly combining all three. Some scenes take too long to get to the point (the fight with the Heffalump), while at other times a segment of the story explaining how a character gained certain information seems to be missing (for example, Madeline’s knowledge of the napping game). ___ The film is in large part too serious and sombre for children, and is even frightening during scenes from the fog-enshrouded Hundred Acre Wood (especially in combination with the red balloon, which is apparently intended as a reference to Albert Lamorisse’s film, but it’s impossible not to recall the psycho clown from It). For adults, the film is sloppy in dealing with the rules of the fictional world, unconvincing with the forced optimism of the conclusion and banal in its approach to psychology (the miraculous transformation of Robin’s thinking), relationships and corporate capitalism. ___ At a time when we need to more vigilantly watch where the current world is heading and act accordingly, the central idea that doing nothing and looking nostalgically to the past can improve our present and that our childhood misses us as much as we miss it is a bit off base (though fully in accordance with the constant churning-out of remakes of old films and the fetishisation of past decades, not to mention that the call to live in the present will certainly resonate strongly with today’s proponents of concepts such as mindfulness). Other films (such as Toy Story 3) have dealt with a similar idea more sensitively. But in the end, this idea was the main reason that Christopher Robin was made and more or less holds together. 60%

Chronic (2015)

Chronic is a film about dying that doesn’t know when it should give up the ghost itself. Franco directs his portrait of a man who lives the lives of others with the same methodical approach that Roth’s nurse takes in caring for his dying patients. The big picture and partial details are presented, but only rarely are there any actual details. The film is made up of long, mostly static shots in which time has stopped. Its flow (and any other movement) has been replaced with coming to terms with the inevitability of death. Our deeper sympathy with the unusually kind-hearted and patient protagonist is hindered by the uncommunicative narrative, which conveys mere fragments of his past and present life. While he is an invaluable pillar of support for the people he cares for, he is far from being well-balanced in his private life. He tries to overcome his own existence through physical activity (running) and by accepting full responsibility for others, who give him the strength to live despite the tragedy he has experienced (which is somewhat paradoxical due to the fact that they are not strong enough to satisfy even their own basic needs). The distance from the indecipherable protagonist to which Franco leads us is partially justified in the conclusion, which offers a highly contradictory yet generally understandable solution to David’s problem consisting in fear of taking responsibility for his own life. Not only the final seconds, but the entire final third of the film, which is entirely more conventional and less focused that what came before, make Chronic an uneven affair. Tim Roth, however, is great from start to finish. 75%

Chuck Norris vs Communism (2015)

Chuck Norris vs. Communism is an excellent supplement to the recent documentaries about Cannon Films (Electric Boogaloo and The Go-Go Boys). It is apparent from the film that watching videotapes of the Golan-Globus duo’s trashy productions helped many Romanians survive the final years of the Ceausescu dictatorship. In and of themselves, the testimonies of people for whom watching Chuck Norris kicking the asses of treacherous Commies was a form of defiance are a piece of honest and useful oral-history work for further research. As would of course be confirmed by domestic witnesses of the rigid era of illicitly distributed VHS tapes in a country with strict censorship and practically no possibility to travel abroad, even the dumbest western film was a welcome escape into a world of luxury cars, unabashed eroticism, brutal violence and stores with shelves overflowing with goods. This level is reinforced and supplemented by both aptly chosen excerpts from films of various quality and genres and staged scenes from the Communist era. The dramatisation, which takes on the style of Romanian New Wave social dramas (the depressing nature of gloomy prefabricated apartment blocks, furtive camera movements, distanced shooting in units), serves to reveal how it could happen that officially banned films entered a country with closely guarded borders. The filmmakers focus on the story of a translator who synchronously dubbed the films into Romanian (and whose fetishized voice many associated with freedom and forbidden fruit), and on an entrepreneur who managed to supply the Romanian video (black) market for several years thanks to money, daring and connections. The smuggling story, which includes the rapid dubbing of Rocky quickie in a dark basement and a hint of a connection to the secret service, resembles a cheaper, though still very suspenseful variation on Graham Greene’s books and thanks to the slow doling out of information, it manages to hold the viewer’s attention for at least the entire first hour of the film, despite the slower pace of the narrative. In the last fifteen minutes, it becomes apparent that there probably wasn’t that much supporting material available and a sixty-minute runtime would have been sufficient. One can also criticise the film for its uncritical adoration of two pioneers of the Romanian video market (facts that would not fit the image of the courageous almost-dissidents are not conveyed) or for depicting the reality of life in a Romanian housing estate in excessively dark colours. In short, the chosen stylisation and the engaging nature of the story are occasionally given priority over the more serious work with substantiated information. However, this does not take anything away from either the mastery with which director Ilinca Calugareanu (who, having been born in 1981, may herself have watched JCVD’s scissor kicks with the fascinated gaze of a child) executes her fusion of documentary and dramatic techniques, or from the richness of the motifs that she succeeds in developing throughout the film: systemic and internal censorship, the economic backwardness of the Eastern Bloc, community life in the housing estates, the relativity of the art that we consider to be valuable. Above all, however, this is an irresistible celebration of the ability of films, even those in which Chuck Norris bites a giant rat, to transport us to another, more exciting and more satisfying reality. 80%

Cisco Pike (1972)

A thin plot, a lot of music, a circuitous narrative, rising disillusion. The easy ride ended in failure and the time came to ease up on the self-assurance and turn a critical eye to the preceding years. The post-hippie process of getting sober hadn’t yet been completed and anyone who wanted to could accuse Cisco Pike of depicting the adoration of soft drugs and their dealers. Nevertheless, the shift away from earlier films emitting the fragrance of cannabis is best seen in the characters. Kristofferson, making his official debut, authentically slacks off on screen as a burnt-out musician forced to collaborate with an undercover cop who no longer embodies the ridiculed or fear-inducing authority figure, i.e. a man against whom laid-back liberals could define themselves. Hackman’s character is not a bad guy from somewhere else, but rather one of those who once belonged to the group and only the whiff of a new opportunity made him betray his previous ideals and stray from the path. Like Cisco and his partner, he could reminisce about the good old days with the nostalgia intrinsic to late-period (Peckinpah-style) westerns. The years when they were respected, when they were somebody. But it wasn’t industrial development that destroyed them, but drugs, drink and dames. Cisco Pike is quite deservedly overshadowed by many similarly conceived minor films by major directors of the same period (Fat City, The Long Goodbye, Night Moves), but it is probably the best work of Bill L. Norton’s later, mostly television, filmography. 70%

Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962)

The anti-Amélie, ungraspable in the manner of the New Wave. Agnès Varda was not a passionate cinephile like the directors from the Cahiers du Cinéma circle. Educated in the arts and humanities, she was less fascinated by cinema than by photography and painting (the paintings of Hans Baldung Grien were a major inspiration for the film’s visual aspect). This is perhaps also a reason that her second feature-length film stands out due to its distinctive grasp of traditional narrative forms (Varda likened her creative process to writing books, calling it “cinécriture”). These forms are neither amplified nor deliberately violated. Instead of adopting or disparaging others’ film language, the director came up with her own way of conveying information to us. Despite her creative grounding in documentary work, this does not involve intuitive directing in the vein of Jean Rouch. Cléo from 5 to 7 has a carefully thought-out concept whose seeming disruption with some unexpected digressions serves the narrative rhythm. ___ The false information about the duration of the protagonist’s odyssey (cinq à sept was an earlier synecdochic term for a visit to a by-the-hour hotel) serves to play a narrative game with two interpretations of time: subjective time and objectively passing time (which is regularly pointed out to us by the clock in the mise-en-scéne). This temporal duality is justified by Varda’s lifelong interest in the relationship between the subjectivity of the individual and the objectivity of the environment, which together shape our identity. She always endeavoured to identify both individual and broader social issues, or rather the common ground between them. ___ With respect to the disregard for standard dramatic structure (exposition, complication, development, climax), the segmentation of the film into thirteen chapters is understandable, as it helps to maintain the brisk pace of the narrative. Three longer intertextual interludes – a radio news report (which also serves to contextualise events in the manner of a documentary), a song and the short slapstick Les fiancés du pont Mac Donald (which is by far the most cinephilic sequence of the film, thanks to the small roles played by Godard, whose beautiful eyes were allegedly the reason that Varda came up with the short, Karina and Brialy) – similarly serve as punctuation marks. The song also bridges the “passive” first half and “active” second haf of the film. ___ Until the singing of the sad song “Sans toi” (written by Michel Legrand), during which the protagonist realises the emptiness of her life and her position as a victim, into which she has been pushed in part by those around her, Cléo is merely an object with a beautiful surface and nothing inside, watched by others and – thanks to the ubiquitous mirrors – contentedly watching herself (a display window full of hats brightens her up the most). The voice, including the inner commentary, belongs to others, as does the centre of the shot, which Cléo only complements with her charm, but she never dominates it. In the second half of the film, she changes from dazzling white to sombre black, takes off her doll-like wig and puts on dark glasses, which enable her to voyeuristically watch others without being watched herself (hiding her eyes makes it impossible for others to ascertain her identity). Later, after removing her glasses, she doesn’t only accept the gaze of others, but also returns it. The camera finally takes her point of view and allows her to see others as objects (the visit to a sculptor’s studio). ___ Cléo starts to stand up for herself. She begins to use her voice and control the fear that has paralysed her. The previous presentiment of death is displaced by a maternal motif (mothers with infants, children on a playground), the idea of life. To put it in feminist terms, the protagonist takes control of her own representation in the second half of the film. She stops giving in to melodramatic passivity and changes the way that she sees herself (while others still see her in the same way, as indicated by the soldier giving her a daisy, a symbol of admiration for feminine beauty). The joyless message at the end of this urban road-movie is ultimately not so devastating due not only to the unspectacular form of its delivery, but mainly due to the paradigm shift. After circling Paris (her route more or less forms a ring), Cléo is no longer an actor in a tragedy to which she can only resign herself. She has found within herself the strength to fight and to take control over which genre her life will belong to. But as the nature of her illness admonishes, this will decidedly not involve full control. 90%

Cleopatra: The Film That Changed Hollywood (2001) (TV movie)

The problem with this documentary with such a bold title is its inability to tell us how exactly Cleopatra changed Hollywood. Though the opening minutes promise a look at the broader context (the twilight of the studio system due to the Paramount Decrees and the rise of television), but the film soon switches to “making-of” mode and the emphasis is placed on the production history and stories from filming (while the source of most of the complications, as they are presented, is not the unprofessionalism, greed or wickedness of those involved, but external influences that people can hardly control, such as the weather and illness). In the case of Cleopatra, there was enough of both to fill up a full two hours. Those who don’t know the details of the film’s creation will not be bored. However, it’s a shame that in the case of a film that perhaps didn’t change Hollywood but at least accelerated certain changes, more attention wasn’t given to the state in which the major studios found themselves at the beginning of the 1960s and which later facilitated the rise of the go-getting Movie Brats.

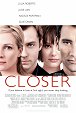

Closer (2004)

“Where is the love?” Scenes from relationship life for the 21st century. Nichols does not in any way try to disguise the film’s theatrical origins; on the contrary, the chosen structure (several long conversational segments), perfectly timed dialogue and classical music accentuate them. It is only after the encounter at the exhibition that he begins to cut between the individual couples’ dialogue scenes, thus giving the impression that their stories are more closely intertwined and influence each other to the point that they cannot be together because of the others (the flashback to the signing of divorce papers, which is interspersed with Dan and Anna’s conversation in the theatre, serves the same purpose). I consider the big jumps in time, which we are usually informed about ex post and as if in passing through dialogue (we’ve been dating for four months, we got together a year ago, he left me three months ago...) to be a courageous decision, as they bring the film closer to a time-lapse documentary that captures only the turning points of relationships. Unlike Bergman, however, Closer is not a carefully nuanced psychological drama, but a contrived melodrama full of walking (arche)types, “chance” encounters and bookish-sounding lines, and throughout its runtime, I wasn't sure to what extent it was aware of its own exaggeration and unnaturalness or the extent to which it was convinced that it was revealing the unvarnished truth about love and relationships, or something along those lines. Many scenes, such as the bitter conclusion, graphically illustrating the fact that we often truly get to know even the most beloved person after they have left us (i.e. when it is too late), suggest that the simplistic characterisation of the characters was a way to convey a universal, almost allegorical story in which everyone who has ever experienced the ambivalent feeling of not knowing whether to kill or fuck the one you love (as in the last dialogue scene of Dan and Larry) can see themselves. So, there is some sort of life lesson to be learned from that. Personally, however, I prefer films that don’t pretend to have depth where there is none. 70%