Reviews (839)

You Were Never Really Here (2017)

With numerous omissions, silences and hints, You Were Never Really Here is a very distinctive revenge flick that explains some things only after the fact (when snippets of flashbacks are put into a broader context) and others not at all. (The narrative, with dynamic cuts in the middle of the action, is highly compressed partly due to the need to shorten it – the budget was slashed significantly in the course of filming.) Ramsay does not in any way romanticise her taciturn tough guy with his numerous wounds on both his body and soul. For her, Joe is a wounded animal (which is aided by the respect-inspiring Joaquin Phoenix, who delivers another full-throttle performance following his turn in The Master) whose actions are unpredictable from one moment to the next. Together with compassion, he inspires fear and you definitely don’t feel very safe during the hour and a half that you spend in his company. The violence, which comes suddenly and is framed without dark humour or ironic exaggeration, is truly painful and unpleasant here, not only because the protagonist’s weapon of choice is a hammer. As the aggression shifts from the level of mere association (bloody handkerchiefs, crushing a piece of candy between his fingers) to something very concrete and very brutal (though the director continues to work brilliantly with evocative sounds and the off-screen space, leaving a lot to the imagination), the sense of danger becomes unbearably acute. The action scenes best demonstrate how the director methodically denies us the genre pleasure of the protagonist’s cleanly done work. We see one of the key bits of action only in static black-and-white shots from a security camera, the nondiegetic music and voices emanating from the television distract us from the brutal fight, and the “grand” climax is highly unsatisfying in terms of (not) fulfilling the conventions of the action genre. So much suffering and despair line the path to redemption that every partial success brings forth bitterness and deepening frustration instead of catharsis. It is simply impossible to enjoy the film, which makes it irritating and fascinating at the same time. Lynne Ramsay has made a stylistically diverse “feel bad” genre deconstruction (like in The American and Point Blank, meanings are communicated through style rather than through the words and actions of the characters), switching abruptly between raw realism, dream sequences and hypnotic intermezzos in which Jonny Greenwood’s aggressive music becomes the focal point. After the film had ended, I wasn’t entirely sure about what happened to whom in the story, what was a bad dream and what was an even worse reality. Like at the end of Good Time, however, I knew I wasn’t going to see anything comparably deviant in the cinema. But I wouldn't be surprised if this admirable exercise in narrative brevity is simply an underdeveloped genre experiment by a director who wasn’t exactly sure what she wanted to make. Perhaps she didn’t know (and the last act was really made up as she went along), but for me, this was one of the most intense cinematic experiences of the year. 85%.

10 Cloverfield Lane (2016)

It would certainly be stimulating to discuss the (viral) marketing of 10 Cloverfield Lane, the 1980s pop-culture references and design (John Hughes), Michelle’s position among other self-sufficient female characters of recent times, the reflection on society’s rising demand for an authoritative leader, or the subversion of the star system by casting John Goodman in a slightly different “dad” role, but for me, this is primarily a textbook thriller that makes maximum use of the information provided within its confined world. Practically every element to which our attention is directed by a longer, close-up or point-of-view shot can be described as compositionally motivated, even though it may at first seem that its purpose is only to amuse us (the infantile shower curtain with a duck motif). Furthermore, in the case of objects that return to the action at greater temporal distance, we are first verbally notified before their involvement in the plot that they have not been forgotten, so that their subsequent use does not feel like a deus ex machina (the bottle of alcohol that Michelle takes from the table when leaving the apartment at the beginning, later mentioned by Howard, and whose star moment comes just before the end). At the same time, the significance of the props is not constant and, for example, the girls’ magazines first notify us that Howard has apparently lost his daughter and are later transformed into part of a staged performance (to reinforce the illusion that Michelle is like Howard’s daughter) and finally into a source of important information that is needed for survival. Every piece of the puzzle is justified sooner or later and it is thus appropriate that even putting the puzzle together turns from being a pastime for the characters into a disturbing clue for the viewer when Emmett ambiguously points out that a few pieces are still missing. And indeed – at the given moment we don’t yet know the whole truth, as will soon become apparent, which makes for a brief, undramatic interlude during which the source of the threat is seemingly lurking just outside. The word-guessing game has a similarly unsettling subtext, using the limiting of the narrative point of view to Michelle – we thus do not know what Howard really knows and, like his two “adopted offspring”, we can’t determine if he’s still playing or maliciously telling them the truth. The seemingly time-killing scene in which Emmett and Michelle talk about their missed chances in life is then absolutely crucial to the film’s meaning, and 10 Cloverfield Lane owes it a lot for the emotionally very powerful and yet – like the whole concept on which the plot is based (three people in a bunker, at least one of whom has a dark secret) – refreshingly simple ending that makes one quickly forget about the unnecessarily spectacular (and, given the tidy confinement of the world in which we had previously found ourselves, disturbing) climax. 85%

After Love (2016)

After Love is the French response to A Separation. Even though the film gives priority to the woman’s perspective, neither partner is portrayed as a villain who would try only to do harm. The problem with Marie and Boris is their unwillingness to listen to each other and their lack of desire to find a shared solution. Through their daughters, however, they not only wage war with each other, but occasionally find reconciliation (a convincingly constructed scene of them dancing together, which will probably make you just as sad as the central couple are that they can no longer be together). In competition with many other dramas about relationships past their expiration date, After Love tries to captivate with its unusual ordinariness. A significant part of the film is made up of the ordinary, everyday activities and interactions of several characters. However, the little things become excuses to bring up old grievances, resulting in conflicts and arguments. Without any major dramatic twists (the film ends with the only, slightly disturbing dramatic event), we gradually come to understand what brought the couple together before and what is driving them apart now (rather a lot of attention is paid to the economic situation of each of them). In my opinion, significant value added is brought to the film by its manner of filming in unusually long shots, with the camera reacting quickly to the characters’ movements, thanks to which the well-coordinated actors do not fall out of their roles (including both of the absolutely naturally acting girls). Despite its parameters of a stifling stage play (for the most part, it involves four actors in one house), the film doesn’t lack dynamism or lightness, and even while maintaining an unsentimental distance, it manages to draw you in, move you and possibly revive your own memories of the long and painful reverberations of what you once considered a constant in your life. 75%

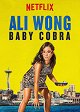

Ali Wong: Baby Cobra (2016) (shows)

Much more than men, women are expected to be congenial and orderly in all circumstances, to yield to the adjective “tender”, which is commonly associated with their gender. Most contemporary stand-up comediennes turn this supposition on its head. A case in point is Ali Wong, who through her performances draws attention to the reverse side of nice things and adds a dark undertone to outwardly innocent activities. For example, when she talks about how she likes to make a snack for her husband every day and then concludes with a conspiratorial remark that she does it so that he becomes dependent on her and never leaves her. The praise of a woman’s life in the household is based on a description of how at home you needn’t stress out about taking care of a major need in shared restrooms with thin, flimsy paper and nearby colleagues trying to dampen their bodily sounds. In describing bodily functions, Wong, like Amy Schumer, examines the issue down to the smallest detail with clinical matter-of-factness. Although she does not talk about human sexuality in a more scandalous manner than her male counterparts, many critics who consider such openness in the area of sexuality unacceptable for women have a problem with such comedy delivered by women. Whether Wong is talking about sex during pregnancy, her racially incorrect dream that she will one day be wealthy enough to buy fruit sliced by white people, or sexually transmitted diseases (she describes HPV as a monster that hides in a man’s body, but only goes “boo!” in a woman’s body), she does not do so in an attempt to shock. She is merely pointing out the simple yet for many not obvious fact that women, just like men, are beings with quite ordinary human needs. 85%

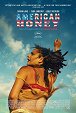

American Honey (2016)

The protagonist’s journey of self-discovery was covered in Andrea Arnold’s previous films, but in American Honey, it is written directly into the unconventional structure of the film for the first time and is manifested both by the choice of setting and the segmentation of the narrative by means of longer musical interludes, during which we enjoy the present moment with the protagonist and do not think about how the film (and the journey) will continue. Whereas Star’s inner liberation happens below the surface, the American landscape through which the protagonist and her companions travel undergoes a significant transformation. Through poetic shots of the setting sun and oil-field fires, we are – like Star – repeatedly pull out of the harsh reality of the lives of those who have who have nothing to lose, which is filmed with an unpleasant degree of detail. Unlike other female wanderers depicted in films, however, Star is not a defenceless figure preyed upon by men. She quickly masters the rules of market capitalism and begins to confidently offer what she has in order to get what she wants. Despite that, the matter-of-factness with which she repeatedly gets into strange men’s cars makes her nervous and raises within her the question of when she will pay for her trustingness. Though the expansive American plains across which the characters travel call for a widescreen picture, Arnold remains faithful to the narrowed academic format. Thanks to that, most of the shots are dominated by Sasha Lane, who also determines who and what we see. The pairing of the energetic protagonist with the movement of the camera gives the film an immediacy and liveliness that grow even stronger during the authentic erotic scenes and other moments when Star lets her instincts guide her. Despite its sensuousness, American Honey is also a merciless portrait of a country in which everything can be converted into a medium of exchange and where you can achieve your dream only if you sell yourself. 90%

Arrival (2016)

If I were able to think like a heptapod (and if events are not predetermined), I would read Chiang’s short story after watching the film. With knowledge of the original story, the film doesn’t manage to be surprising with respect to what it aims for from the beginning and what it so much relies on to its own detriment. ___ Whereas Chiang gets straight to the point, Villeneuve understandably dedicates much more space to exposition. The first encounter is thus preceded by a comically long “build-up”, during which the protagonists fly in a helicopter to Montana, put on protective coveralls, drive to an enormous spaceship, climb onto a lifting platform, ride the lifting platform (because we would be deprived of one dramatic ride if the platform stood directly below the opening) and walk into the bowels of the ship. The only function of this procedural porn is to prepare us for an essential and epic reveal which, however, doesn’t happen, because all we learn from it is what the aliens look like. The individual steps leading up to the act of communication don’t play any more of a significant role later. For me, the entire film was such a similar unfulfilled promise as the scene described above. ___ The long and slow opening sequence is also unsatisfying in introducing protagonist, whose actions throughout the rest of the film can probably be explained by the fact that she lives alone and compensates for her poor personal life with work (she is the only one who goes to school even when the rest of the world is experiencing an alien visitation). Many of the informative dialogue scenes, flashbacks with the child and the scene in which Louise translates a conversation in Chinese so that we know she also speaks Mandarin, feel similarly utilitarian and inorganic. The coldly engineered approach to the characters, who remain mysteries like the alien logograms until the end of the film, wouldn’t matter so much if it wasn’t in conflict with the melodramatic level of the narrative, which is based on the relationships and motivations of the protagonists and becomes dominant in the end (I consider the replacement of an accident, which perhaps could have been prevented, with an incurable disease, which can only be accepted as an inevitability according to melodramatic conventions, to be quite essential). ___ In the short story, a theory that is partially revealed is continuously applied to a universally comprehensible story whose main purpose is to make the heptapods’ way of thinking comprehensible. The aim is thus not to move the reader, but to help them understand how “it” all works. Conversely, the newcomers attempt to offer emotional rather than intellectual satisfaction, but they’re not very successful. However, Arrival is still a skilfully made sci-fi movie about the importance of (mis)understanding, though it is too reminiscent of Interstellar due to its expository dialogue, extremely serious tone and cold visual style, but I wasn’t as impressed with it as I was with the short story. Among other things, that is due to how doggedly it tries to astonish the viewer. Postscript: If the solution presented by the film for reuniting a divided world is the only one possible, then we’re pretty much fucked. 70%

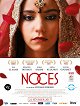

A Wedding (2016)

The opening shot, which presents to us the bare facts without equivocation as the main female protagonist conducts an “admission interview” at an abortion clinic, is likably bold and matter-of-fact. The rest of the film is neither. A Wedding tells a clichéd story about religious traditions that – especially for men – are more important than individual happiness. It does so in a not very economical, but very predictable and simple manner (just in case we somehow don’t understand from their life stories, two female characters carry on a dialogue about how difficult it is for a woman in a family clinging to tradition). The perspective of the parents and the brother is taken into account not so that we would have greater understanding for them (as in the recent The Big Sick, for example), but so that we understand that they understood nothing and were more concerned about Záhira (I haven't seen such clumsy use of the “Chekhov’s Gun” principle in a long time). A Wedding merely insensitively asserts the stereotypical image of Muslims as religious dogmatists who resist women’s emancipation and progress in general tooth and nail. Last year's Hedi, for example, managed to make something special out of a similar narrative formula with a civil concept and political subtext. In Streker’s melodramatic film, which takes only extreme positions (hysterical father, grand speeches about the loss of honour, references to an ancient tragedy), only the excellent Lina El Arabi in the lead role comes across (and acts) naturally. Without her, it would be truly difficult for me to find a reason to attend A Wedding. 50%

Beware the Slenderman (2016)

This documentary is disturbing in multiple ways. It starts out as a fascinating case study of a very topical issue – the tendency to become enclosed in social bubbles and the creation of an alternate reality based on fallacies spread over the internet. However, the director gradually abandons the Slenderman level in order to focus on the attackers, or rather their families, which takes a toll in the form of numerous emotive shots of crying faces that do not reveal anything. In the end, the girls who brutally assaulted their peer eventually emerge from the documentary as victims (of the internet, of the group, of psychological disorders, but not of a haphazard upbringing). The serious nature of the crime remains in the background and the actual victim does not get nearly as much attention as the accused, who, thanks to this film, basically become celebrities whose “legend” will in all probability spread on certain internet forums just as the legend of the Slenderman did (see the fan drawings of the two girls holding knives). I consider the capitalising on the Slenderman myth to be even more problematic than the reversal of the roles of attacker and victim (which is perhaps partly due to the American media culture’s fascination with criminals). Instead of the film clearly declaring that it is about stories aimed at scaring teenagers, it attempts to create a horror atmosphere with photographs and videos of Slenderman set against a background of disturbing music. As a result, the documentary (probably inadvertently) does not deconstruct the myth while keeping a reasonable distance, but rather aids in creating a myth without any such distance. I would not be surprised if there is an increasing number of people who, having seen the film, start seeing a tall, faceless man with tentacles on his back in various places. 50%

Blood Father (2016)

Blood Father is a pleasantly straightforward revenge thriller. It will serve the purpose for a Saturday evening on basic cable, but for fans of B-movies that don’t deal in a large amount of profanity and a high body count, it probably won’t offer the same satisfaction as movies that are even more uncompromising and lay claim to the trash tradition with greater pride (such as Gibson’s Payback). Richet manages to limit the theatrical dimension of the father and daughter reuniting and bonding by treating the central duo’s relationship a bit like a buddy movie, but despite all the cynicism and dark humour (see the opening joke about buying bullets, which of course fundamentally conflicts with how uncomplicatedly guns are dealt with in the rest of the film), it is still apparent that family and forgiveness comprise the theme of the film. Due to the short runtime, there is fortunately not much time for didactic dialogue and, furthermore, Gibson’s father character brushes off most of his daughter’s sins with the word “fuck” delivered with various intonations. Richet knows when to crank up the narrative with an action scene and, despite the predictability of the plot, he manages to surprise us a few times with an unexpected cut (to what is happening in the film projected in the cinema) and the agitation with which casual conversations are shot and edited (so that we are constantly aware that the characters are under time pressure). ___ If some roles are said to have been written directly on the actor’s body, in this case that is undoubtedly true (although the film is based on a book) and I find the autobiographical aspect to be the most inspiring part of the whole film. Gibson plays a recovering alcoholic, a former member of a biker gang who has had so much trouble with the law that he risks violating parole with even the slightest offense and going back to prison. He hides out in a western no-man’s land near the Mexican border, staying away from a society in which he has lost faith. Only his daughter in distress compels him to dust off his soldier mentality and lethal skills, which in the end are not something he should be ashamed of, but a useful insurance policy in case of emergency and a reminder of a time when he actually lived (not just survived). You never know when a group of angry Mexicans (it must be said that, to the film’s credit, neo-Nazis are also a threat here) will come to shoot up your camping trailer and you will have to take justice into your own hands. Your problematic past will come in handy in such a situation. As long as you help your family, it doesn’t matter how much damage you do or how many bodies you leave behind. In other words, if – like Mel –you were once a bad guy, that doesn't mean that you should suffer for the rest of your life because of it. It’s unlikely that Blood Father will be the film that saves Gibson’s career, but it offers a lot more (guilty) fun than other projects that are basically just psychotherapy for the actor or filmmaker. 65%

Bridget Jones's Baby (2016)

“You turn disasters into victories.” Bridget Jones’s Baby is a mostly successful attempt at making a tasteful romantic comedy for adult viewers that will make you forget the dreadful second Bridget Jones film while remembering the best of Working Title’s genre productions. However, the filmmakers try too hard to fulfil high expectations, which becomes apparent in the excessive runtime (and the resulting problems with pacing), and to play it safe (e.g. impressive but not very effective slow-motion shots and the autotelic inclusion of catchy pop songs). What we see is basically the third variation of the same story template, which is very predictable from start to finish despite the addition of a new unknown feature (the unborn child). Nevertheless, the film offers some surprises at least with small things like the generally believable behaviour of all of the main characters (Bridget finally acts in accordance with her age), who are able to reflect on their idiotic conduct (Jack apologises for lying to Mark). The incomprehension of today’s world of internet dating, photos of cats resembling Hitler, hipsters and Pussy Riot may not be as striking as in Marie Poledňáková’s films, but in places it is still painfully obvious that the filmmakers are stuck in a different era and are trying in vain to catch up with the times. What works best are the universal jokes on the topic of “men vs. women”, most of which co-screenwriter Emma Thompson stole for herself (a great line involving childbirth and a burning pub), that you will remember days after the screening. But you probably won’t remember much else. 70%