Reviews (840)

Captain Fantastic (2016)

This typical “Sundance movie” is a feel-good tragicomedy with a nice soundtrack, eccentric but likeable characters and a predictable ending. The raw opening scene depicting the first of a series of rituals aimed at preparing Bodevan for his entry into adulthood gives the viewer hope that Captain Fantastic will be more truthful than ingratiating, while not offering any wonderfully easy solutions to complex problems. But from a celebration of life outside of the system that strips people of their individuality, the film soon collapses into a hackneyed story about the necessity of socialisation and respect for social conventions. The characters may not be willing to accept the norms of the world that they have scorned for so long without question, but their transformation is still tied to their subordination to the dominant ideology. Though the director sensitively spreads the attention among all of the members of the family, led by Mortensen’s practically perfect protagonist (whose mythologisation, already evident in the film’s title, is not problematised by Ross), he cannot disguise the fact that his characters serve mainly as walking arguments in support of the conservative idea of the importance of a happy family. Thanks to its pleasing shot compositions, slightly cynical humour, reasonable amount of pathos and well-timed use of upbeat music, the film evokes the intended emotions, but these quickly fade, because Captain Fantastic is not built on a convincing foundation. We can believe neither in the characters, who too easily give up everything they have fought so long and hard for, nor, because of that, in the would-be non-conformist, anti-consumerist message. 70%

Jane Eyre (2011)

- I dream. - Awaken then. Jane Eyre is a mature synthesis of two “women’s genres”: melodrama and gothic horror. The narrative complies with the intentions of feminist discourse, taking into account the numerous restrictions that 19th-century women had to overcome, while not hyperbolising them to such an extent that the film would become another hopeless story of female suffering. The protagonist is self-confident and conscious of her abilities, and her calm dialogues with her “master” do not correspond to the traditionally depicted relationship between superiority and subordination. Cautiously being in love without fully giving herself over to her partner blunts the sentimental edges of the melodramatic level and makes it impossible to watch Jane Eyre as a straightforward tear-jerker. Fukunaga’s adaptation uses the classic novel to pose topical questions without doggedly striving for modernity in any other aspects of the film – cinematography, production design, the characters’ vocabulary. In other words, the film’s creators interpret the original novel as people instructed by developments in thinking about the social position of women, and as such logically project into it what Brontë could only consider to be a utopia in her time. Thanks to that, the film achieves an extraordinary balance between the modern and the classic. 85%

Husbands (1970)

Husbands comprises a trio of interrelated character studies that, taken together, offer an honest portrait of a crisis of middle age and of the middle class, which fails to respond to rapid social changes. Cassavetes took his “direct cinema” directing style to the extreme with this autobiographical bromance, which was supposedly intended to help him get over his brother's death. In long, seemingly unscripted takes, he lets the camera watch the actors deal with emotionally complicated situations. Instead of Gazzara, Falk and Cassavetes himself reciting their lines in predetermined positions and in clearly composed shots, the camera has to busily respond to their unpredictable movements. They often have their backs turned to the lens or they stand so close to it that their faces are blurred. This is probably the reason that Cassavetes practically does not use analytical editing, dividing the film space into separate sections (establishing shot, shot/counter-shot), but instead prefers objective shooting, which is not bound to the perspective of any of the characters (however, the film quite clearly adopts the perspective of the trio of protagonists, as is obvious from its politically incorrect machismo – we either don’t see the men’s wives and other women at all, or we see how they are battered and used for the satisfaction of men’s desires). The maximum trust that Cassavetes places in the actors puts his method at the opposite end of the spectrum from the signature style of Alfred Hitchcock, who had every movement of his actors under his complete control. On the one hand, the subordination of form and style to the actors reinforces the impression of spontaneity, the impression that we are watching an unmanipulated situation as it unfolded during filming; on the other hand, it leads to such laxity of the narrative that it becomes irrelevant how many minutes have passed and how much longer the film will run. It wouldn’t be entirely fair to say that the film deserves the “home video” label due to its narrative structure and its aesthetics, but, in my opinion, Cassavetes went too far by not employing a narrator who would lead the characters from somewhere to somewhere. Clearly, my perception of films is excessively burdened by the need for a concise, "classically Hollywood” plot, and I cannot greatly appreciate a work that primarily tries to depict a certain state of mind (the entire film can be seen as an attempt to fill an empty space and escape the fear of the future initiated by the opening funeral). 70%

A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

How should I behave so that others consider me, an exemplary mother and wife, to be normal? That’s a banal question, but try to act it out. I’m interested in knowing what kind of environment the director grew up in, as the absolutely unrelenting arguments that he has filmed are as authentic as a home video (which is due in part to the intrusive camera, which makes it difficult for us to find our bearings in the space by shooting close-ups of faces, which is a signature aspect of Cassavetes’s style). The actors are largely to thank for this. Falk is perfectly typecast in the role of a simple guy. The self-destructive use of Gena Rowlands, who is as fragile inside – despite some powerful gestures – as the bonds she tries to forge with the world around her, is impossible to just coldly watch, even if you reject her character as such. Those around her perceive her as a headcase, without anyone bothering to address the causes of her erratic behaviour. Unspoken concerns and the fear of facing problems head-on depress the direct participants (in quarrels) and disturb the passive witnesses, which naturally does not lead to a solution. It is fascinating and exhausting to watch psychologically tense situations for two and a half hours, but it is impossible not to question the meaning of it all. Extraordinary cruelty? Ordinary sadism? 85%

The Punk Singer (2013)

This playful, fierce and dynamic (like the music we hear in it) portrait of one of the icons of the third wave of feminism draws on the collage-like aesthetic of riot grrrl, the punk-rock movement that Kathleen Hanna co-founded. Sini Anderson spent four years with the vocalist of the feminist band Bikini Kill, which was long enough to lose critical distance from the subject of her documentary (not to mention that the two women had known each other for a long time before shooting began). Despite the themes that give rise to powerful emotions (abortion, rape) and lead to emotional blackmail (an illness that prevents you from doing what you have devoted your entire life too), The Punk Singer nevertheless maintains a praiseworthy degree of matter-of-factness. Though it portrays Hanna in a mostly positive light as an inspirational figure with admirable energy, it doesn’t make her out to be a bigger heroine than is necessary. The last twenty minutes dealing primarily with the singer’s illness are no exception, yet the focus remains on the broader context. The entire film is built on the intertwining of the personal and the political in accordance with feminist principles, incorporating the activities of Hanna and her colleagues into the history of the struggle for women’s equality. The history of feminism is understandably presented in a very simplified form, giving the impression that the third wave of feminism comprises an ideologically coherent group of activists with uncompromising punk rockers at its core. The incorporation of feminist ideas into the mainstream beyond music and the commercialisation of feminism (if it weren’t for bands like Bikini Kill, it is probable that the Spice Girls and Pussycat Dolls would have never existed) are left aside. Similarly, the singer’s double-edged treatment of her own body as a sexual object (which Madonna takes to the next level) is not problematised in any way. The film cannot be reproached for offering little impetus for such considerations, which bring more ambivalence into the final result; it only depends on the willingness of each viewer to think and seek out information beyond what they learn from The Punk Singer. 80%

Green Room (2015)

After Blue Ruin, this is a step back, even if we approach Green Room as an old-school, low-budget slasher flick (with well-thought-out camerawork instead of an attempt at raw docurealism, “handmade” gore effects instead of CGI) rather than as a metaphorical commentary on a society divided into ultra-far-right psychopaths and left-wing anarchists. Green Room doesn’t offer the slow build-up of suspense found in Saulnier’s previous film. Indeed, there is none of that in this film, which generally feels like someone just made it up as they went along. There is nothing here to give rise to suspense. The mechanical stringing together of attacks and counter-attacks is preceded by a rushed exposition, during which we don’t learn enough about the protagonists; we don’t even remember their names, let alone take an interest in them and later fear for them. Whereas in Blue Ruin the minimisation of psychological depiction of the characters and the concealment of certain information served to give the story a degree of suspense, here those aspects are a manifestation of helplessness in fulfilling a deceptively simple concept. The ensuing orgy of violence, whose justification is not in any way problematised as it was in Blue Ruin, may get your blood up a few times (see the blatantly shocking abdominal slashing), but it fails to make an emotional impact. Besides that, the characters on both sides of the solid door too frequently behave like idiots to be a welcome enhancement of the “conquest” formula as we know it from Rio Bravo or its remake, Assault on Precinct 13. Mistakes with deadly consequences are made by both civilians and “soldiers”, thus blurring the differences between the two groups, and Pat’s story lacks the intended resonance in furthering the narrative. The most unfortunate thing is that the characters are unable to use their advantages, whether that involves a loaded gun or numerical superiority, basically just so that the runtime can be artificially stretched out to an hour and a half. If they made more reasonable decisions, the film would probably have been shorter, but also significantly more boisterous. All of the rawness is diminished by the retarded (and mind-numbing) dialogue that tries unsuccessfully to give the impression that, all things considered, it’s not only about who kills whom first. The characters are forced to choose complicated solutions (why use guns and an army when I can send two guys in with pocket knives) just so that they can die slowly and more painfully. As a result, Green Room is neither an intoxicatingly simple genre flick nor “something more”. 45%

Blue Ruin (2013)

An intense feeling of unease from start to finish and long after the film has ended. Blue Ruin (a more fitting title might be “I Piss on Your Grave”) works flawlessly as a pure, visceral revenge movie (probably without “rape”, but that’s not entirely clear). Saulnier restricts the not very communicative narrative’s scope of awareness to what the protagonist perceives and feels. The soundtrack disturbingly mixes subjective auditory perceptions with the actual sounds of the setting, so we are never sure if a real threat is approaching or if Dwight is just humming in his head. The realistic details (pulling out an arrow, turning off the water and switching off the light, stress-induced vomiting) also play a significant part in the emotional absorption, making us aware that the rules in this world are quite similar to those in our world (which may sound like a banality, but it is definitely not an established standard in American genre films). Only the characters here act with animal instinct according to the elementary evolutionary model of “kill or be killed”. Like good old cowboy movies, where there was no room for drawn-out consideration and speeches, where the conflict between civilisation and wilderness (here directly embodied in the main protagonist, standing on the boundary of these two spaces) was also an eternal issue to be confronted, and where guns were also the most popular fetishistic object. One might have reservations about the overly fleeting indication of motivations, but the minimum amount of information about who and what so badly messed Dwight up contributes to disturbing doubts about whether his actions are justified. The film does not provide an answer. It just thoroughly unsettles us and leaves us to somehow come to terms with all of the conflicting ideas in our own heads. For me, this is a clear sign of a high-quality thriller. I’m looking forward to Green Room. 80%

Horace and Pete (2016) (series)

“I'm living with a broken heart and I'm drinking and one of these days it’s going to kill me.” Television executives wouldn’t try viewers’ patience with the unnerving knowledge that anything could happen. Louis C.K., however, based his latest project on doing just that. In addition to the varying lengths of the episodes, the uncompromising treatment of the characters, the slow pacing and the theatrically minimalist style, he refuses to submit to the demand for exuberant and immersive television entertainment by making only minimal changes to the setting and the size of shots. The characters rarely leave the interior of the bar and even more rarely are they filmed other than with a static camera in half- or full-body shots. The artificiality of the set decorations is not hidden in any way. On the contrary, it is pointed out to us, which paradoxically adds emphasis to the genuineness of the emotions and the liveliness of the dialogue, which can touch a raw nerve and, thanks to the actors, does not have the hallmarks of theatricality, unlike everything else. C.K., however, maintains Aristotle’s unities of time, place and action, particularly in order to surprise us by abruptly violating them during the transition from reality to the unrealised sexual fantasy of one of the characters or a leap of many years back in time. ___ Though the series, with its maximally spare design bordering on amateurish, is rather more reminiscent of a thirty-year-old sitcom than a representative of the current wave of high-quality TV, the production of each episode cost roughly half a million dollars, which corresponds to the budget of a low-budget American indie film. Less than two months after the last episode aired, however, C.K. could boast that the series, with its many well-known actors and music composed by twelve-time Grammy winner Paul Simon, was already in the black. What’s more, this was done without the aid of traditional marketing and without using existing television or internet platforms. C.K. basically did it all by himself, as the degree of his creative input is truly exceptional. Though C.K. wrote, filmed, edited and produced the series, as well as playing the lead role, he does not push his own character to the forefront at the expense of his castmates, and he keeps a significant critical distance from the character of Horace, not giving him any more opportunity to do something than the others are given. The comparable weight of the individual characters’ voices is bound to the central theme of open discussion – the titular bar serves as a form of communication on social media, where everyone has an opinion and stubbornly defends it without regard for the arguments of others. C.K.’s willingness to suppress his own ego is also evidenced by the unusually generous space devoted to the dreams and wishes of the female characters, who act with greater determination than the men. ___ Horace and Pete deals with adult themes and doesn’t attempt make light of situations at all costs: life takes unpredictable paths, people die and (consciously) hurt each other, romantic ideas of love have long since faded, and the search for a way out leads to nowhere. Instead of trying to entertain us, Louis C.K. reminds us that we will also die someday. I can’t imagine a series like this getting approved by any of the established TV or cable channels (or Netflix or Amazon, for that matter), but I now know that something like this is not unthinkable. 80%

Independence Day: Resurgence (2016)

“They like to get the landmarks.” Though it would have been good for it, Emmerich’s new movie doesn’t contain many more similarly prescient lines, and it does show any awareness of its own bullshit. The gravity with which the subject matter, reminiscent of a 1950s sci-fi B-movie, is handled gives one an idea of what Starship Troopers would have looked like if Verhoeven had taken it seriously. With a guilelessness that’s as endearing as it is disturbing, the new Independence Day turns the message of the Cold War-era The Day the Earth Stood Still on its head. A more advanced civilisation is not here to warn humanity of the risk of self-destruction, but to help it destroy the enemy. The purpose of war is not for people to learn from it, but to better prepare themselves for the next war, because without warfare the military-industrial complex would logically collapse. Solutions other than military force are not even considered and the effectiveness of using hard power (even against an ally) is not in any way questioned by the film’s message. It doesn’t explain why society was divided, but mainly shows that society was united by waging war. Military conflicts thus essentially have a positive effect, even if they usually result in a few major cities getting wiped off the face of the earth. Even though I am disgusted by the ideology that the film expresses (not to mention the character of the exceedingly incompetent president), and though its sentimentality and patriotism sometimes exceed the tolerable limit, I enjoyed the second Independence Day as much as I did the first one. In terms of composition, it is a perfect summer blockbuster in which every motif and every character has its own justification (and the extended exposition thus bears fruit later in the film). The multitude of characters allows Emmerich to change the point of view as needed and thus share with us information that is necessary to keep us in the picture while wanting to know more (by the time we get to the climax, we sense that there will be a snag, as all of the plot lines have not been resolved yet). The film is brilliantly paced throughout, including at the level of individual action scenes. The deadline that we are continually warned about comes ever closer, the aliens get bigger and stronger, the number of important characters in peril increases. The $200 million budget is evident and the battles are massive, but neither would matter if the action wasn’t a solid part of the narrative, helping to move the story along by eliminating certain obstacles and creating others. If you are going to make a big, dumb and not very original sci-fi flick, then do it with the storytelling skill found in Resurgence. 80%

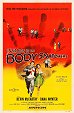

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Once you start having doubts... It’s as if the disillusionment of film-noir has shifted from the big cities to the suburbs. Like post-war American society, preventively haunted by spies from the East and the atomic bomb. A unified consumerist society. The first major critical success achieved by Peckinpah’s mentor, Don Siegel, is sadistically disturbing due to the fact that it explains nothing. He doesn’t use his depiction of the mood in society for the purpose of making transparent anti-communist agitprop. Instead, he places innocent situations that were surely familiar to Americans at the time, such as backyard barbecues, in a deliberately vague context, thus forcing viewers to figure out for themselves what is wrong, and what is wrong with the viewers themselves. The rational explanation that the characters seek from the start is non-existent. Try explaining fear. Where a psychologist cannot cure an individual, no institution can help society. They are all in on it and anyone who tries to get out of it will be taken as a fool. The confining atmosphere is due in part to the camerawork, which intrudes on the characters’ personal space, and the use of locations that minimise the chance of escape (corridors, narrowing streets). The occasional naïveté and half-baked nature of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is amusing today, but these aspects are not so frequent and conspicuous that they would negatively affect the film’s astonishing momentum, a third of which is derived from the unceasing escape from the situation that people found themselves in at the time. And actually not only then. 85%