Reviews (839)

Gangs of New York (2002)

“The blood stays on the blade.” With Gangs of New York, Scorsese dug deep into the past while picking up the threads of Goodfellas and Casino, compared to which Gangs has a somewhat more conventionally constructed story, though it unconventionally depicts two rises and only one fall. The streets on which the plot is set are mean this time and we don’t have to refer to swine in only a figurative sense in connection with them. Dickens’s protagonists would have been right at home in them. After all, one such protagonist stands at the centre of the narrative (and speaks to us through the essential voice-over). Unlike Oliver Twist, however, he doesn’t learn to steal from his victims, but to beat, stab and slash them. Marked by his strict Catholic upbringing (what else?), Amsterdam Vallon serves as our guide. We learn through him what happened when a certain social class in New York lived the final years of its age of innocence. The young protagonist serves as a harbinger of the oncoming end of the era of men who wanted to always have the last word even though they knew only how to fight and diplomacy was a foreign concept to them. After he finds his footing and joins a gang, he can start working toward his primary goal: to avenge his father. In order to achieve that, he must kill another father figure (with whom he shares a woman in an Oedipal way), a psychopathic butcher who dresses like Willy Wonka (though he is otherwise characterised by a diabolical shade of red) and doesn’t make much of a distinction between the flesh of humans and animals. Only an unsuccessful assassination attempt and the subsequent punishment cure the protagonist of his selfishness and force him to play a more significant role in events. After Amsterdam’s revival, the film starts anew, which justifies the expansive runtime. Just like the other characters, however, Amsterdam is repeatedly confronted with the cold, hard fact that his problems and the trivial war that he is waging are losing significance (which egotistical men assign to it) in the shadow of ongoing major events and the Civil War. At the same time, what’s happening in Five Points is a local reflection of national events: on both levels, two Americas are at war with each other. The “pure” America of conservative native-born residents and the new multicultural America of immigrants. The victory of the latter heralded how not only New York would look a few decades later, but the whole United States (the character of Bill the Butcher, who takes a little from the divider of the people Abraham Lincoln and a little from George W. Bush, another powerful figure who brings about order through fear, invites a search for other political parallels). The film not only ends with the blending of the past and the present, but also begins, though the present is represented only by non-diegetic music in the opening brawl. It’s obviously not necessary to spend a lot of time writing about Scorsese’s skill as a director. He knows exactly when to use a lap dissolve, when to use views from above and below, and when to throw in a jump cut to keep the film moving while bearing his unmistakable creative signature (even here, the setting is presented in a single long shot in the mould of direct cinema documentaries). Proof of all of this can be found in the boxing match with flawlessly timed cuts between the medium shots, when the fighters are in motion, and the close-ups when they deliver blows. Scorsese has again demonstrated a tremendous eye for detail and an ability to thoroughly get a feel for any place and any period (whether temporally or culturally), no matter how remote. Instead of television footage and period songs (though these are also present in the film), he uses leaflets and newspaper articles from the period. The slang used by the street rabble is authentic and the impression of a different time is disrupted mainly by the famous actors. By that, I of course don’t mean to insinuate that I wouldn’t enjoy watching, for example, Daniel Day-Lewis tapping his own glass eye with a knife. Gangs of New York is a great film that doesn’t shy away from showing that the hands that built America were thoroughly soaked in blood. Given the post-9/11 atmosphere at the time of the film’s release, the ending is gentler than Scorsese would have otherwise allowed, but I think a little gentleness is justifiable after two and half hours of epic slaughters. 85%

Kitchen Stories (2003)

“What the hell do you have on your neck?” “A scarf.” “A scarf with a tail?” “Yes, with a tail.” Folke is allowed to do what perhaps every film viewer would welcome – to intervene in the life of the person they are watching. Empathy prevents him from remaining in the role of observer and so, understanding that some facts simply cannot be entered in a table, he not only exchanges snuff with the subject of his research, but also trades places with him. The secondary alternation of the roles of the observed and the observer is ultimately a more original feature of the plot than the central coming together of two men, or rather two cultures. I actually and rather selfishly regretted that the long-silent Norwegian and the long-silent Swede found their way to each other and began conversing about fundamental question of humanity, though it’s true that their conversations are marked by charming simplicity and with an added bonus in the form of random bits of absurdist humour. The film doesn’t abandon the calming atmosphere of Scandinavian moderation after that, but the admiration for the minimalism of Hamer’s film language is replaced by waiting to see how firmly the screenplay adheres to the anticipated plot development. Firmly indeed. 70%

The Illusionist (2010)

Tati’s non-aggressive style of comedy, when Mr. Hulot often disappears somewhere in the mis-en-scéne, has been elevated to the level of the main theme in The Illusionist. The protagonist stands at the edge of the picture and edge of interest. If he doesn’t find a kindred spirit in a dreaming girl, no one will notice him; he is almost invisible. As with Hulot’s magic, with Tati everything is always hidden somewhere around the corner while also being omnipresent. The comedy arises from seemingly (given that this is an animated film, really seemingly) random situations – the wind blows open a wind and it starts raining. The gags do not show off their sophistication, but simply just happen. Chomet opens before us several doors at once and doesn’t warn us in advance that someone is coming through them. Just as Tati creates a particular situation and leaves it to develop and reverberate. He doesn’t rush, though the average shot length is obviously (even without using a stopwatch) shorter than in any of Tati’s three masterpieces. He references not only those (for example, the contents of the washed car’s trunk remind us of Mr. Hulot’s Holiday), but also the wrongfully ignored Traffic (the deluge of black umbrellas) and the circus-themed made-for-TV movie Parade. The reference that shines through most in the film, however, is My Uncle, whose plot The Illusionist paraphrases. There is more definitiveness this time only in Hulot’s final passing of the baton. His yielding of space to the youth inside him is marked with both bitterness and hope. The illusionist leaves, but the illusions – at least the cinematic ones – remain. Chomet doesn’t change Tati in his own likeness. He retains the characteristics of Mr. Hulot as an old-fashioned element that is sometimes disruptive in the modern world and who understands children but not technology, but he allows him to look at himself from the outside (literally in the scene from the cinema). I consider the most eloquent aspect of this virtually silent tribute to the last of the masters of slapstick to be the parallel micro-story of a sullen, world-weary clown who is more fascinated by the movement of machines than by the movement of living beings. Alone, neither human nor inhuman, not fitting in anywhere. I believe that Tati felt something similar. 85%

The Flying Saucers Over Velky Malikov City (1977)

A comedy of extraterrestrial origin, made by beings who have no idea that there should be at least elementary causality between adjoining shots; that the behaviour of the characters, if they are at least reasonably intelligent human individuals, usually exhibits a certain amount of logic; or that comedy should elicit laughter rather than the urge to destroy the TV screen with a hammer and sweeten your coffee with arsenic. But seriously – WHAT THE FUCK WAS THAT??? 10%

The Ladykillers (1955)

Five nobodies who are dangerous to themselves and one lady who is so nice that one could kill her. The perfect setup for a comedy in which a life is at stake. For light entertainment, The Ladykillers is superbly directed, which is true of both the comedic and thriller scenes. The deaths are chilling. The characters, who represent a caricatured sampling of English society at the time, are not treated with any respect, though it can’t be said that they would deserve any. If the ossified generation overpowers the up-and-coming generation, it is not because of their resourcefulness, but because of their inability to come to an agreement with others. This, the last great film of Britain’s Ealing studio was successful not only in its country of origin, but also in the United States (most likely because of how biting it is in comparison with Hollywood movies of the day), to which director Alexander Mackendrick was also lured by Sweet Smell of Success two years later. Appendix: What was essentially British about the original comes through in the Coen brothers’ successful remake, which shifted the plot to the American South, dispensed with the cold-blooded moments and reached for more straightforward humour. 80%

Shutter Island (2010)

“I’ve seen something like it before.” I’m going to throw out some spoilers, so it would be better if you read this after seeing the film. On the first viewing, until the lengthy explanatory passage, Shutter Island is a paranoid crime thriller that draws on Hitchcock’s legacy and horror B-movies. On the second viewing, it is an atmospheric drama laden with the questions that Scorsese has posed throughout his entire filmography (What’s worse, emotional or physical violence? Is it better to stay in one’s accepted role or to reveal one’s true face? To accept guilt or let it consume you?). Unfortunately, the second viewing reveals not only the well-thought-out distribution of clues leading us to the final revelation, but also the film’s inability to work on both levels simultaneously. The pleasure of a skilfully shot, though not entirely smoothly flowing genre movie (the shots don't fit together as elegantly as in Casino, for example) is disrupted by long dialogue scenes in which the Big Issue is addressed, which Scorsese is again unable to properly elaborate on, because he would deprive himself and us of the pleasure taken from the presence of trashy add-ons like Nazis, mass murder, a mysterious lighthouse and a lobotomy. In short, he spoils the fun by trying to squeeze something more out of it, which is manifested in the significant reduction of the funny verbal exchanges between Chuck and Teddy from the book on which the film is based (and which, incidentally, can be read in one breath both as a genre treat and as a suspenseful story that may conceal something more). Therefore, I find it more inspiring to watch Shutter Island, even at the cost of a slight overinterpretation, as a multi-level psychoanalytical treat for all followers of Žižek (Teddy constantly moves between different floors, which we can see as “levels” of his mind; familiar with Teddy’s dreams, Dr. Cawley personifies the subconscious; Chuck, addressing Teddy as “boss”, conversely represents his – seemingly – controlled ego) which with its narrative is – probably unintentionally – reminiscent of a video game (restarting the mission, collecting objects and solving riddles, Teddy as Laeddis’s game avatar…). Choose what makes more sense to you. Regardless of its faults, one visit to Shutter Island will almost definitely not be enough. 85%

The Age of Innocence (1993)

“I want, and I can’t.” More than two hours of filmmaking elegance at a level that few directors manage to achieve. I didn’t get the impression that the plot was conventional and that only the rendering of it was extraordinary. Both aspects are beyond the average and both logically complement Scorsese’s filmography. Though The Age of Innocence is actually another one of his films about violence and organised crime, the violence and crimes in it are hidden, unmanifested. The rules of behaviour are determined by clans, though not mafia clans in this case, but familial clans. Those who do not want to lose their prestige, as if anything else mattered, must not mention that fact, nor can they even think it. The characters harm themselves with words, or rather by avoiding words. As in the book on which the film is based, their true intentions and repressed desires are revealed to us by an honest narrator, a physically absent yet omnipresent guide to the now so distant world of the New York upper crust in the late 19th century. The narrator says what the characters dare not say. Together with the setting, she speaks for the silent protagonists (I had assumed that sophisticated work with colour, props and blocking had gone extinct along with classic Hollywood – fortunately that is not the case). In the diegetic world, Countess Olenska takes on the role of a woman who does not intend to conceal the state of things as she has come to recognise it. She does not want to be another victim of social conventions, another obedient, loving wife. However, she doesn’t have immunity to protect her from the impact of her frankness. The power to save her belongs to Newland, who is consumed from within by the necessity of choosing between a woman who speaks the truth and a woman who says only what is appropriate. Thanks to the narrator, the (post-)modern narrative techniques (letters read to the camera, the director’s self-reflexive cameo as a photographer, the one who records the lives of the characters) and the careful guidance of our attention (through music, making words visible and the moderate use of close-ups and “archaic” curtains), we clearly and comprehensibly learn more about the characters than the period and setting in which they lived allowed them to learn about themselves. More than relationship dramas that focus primarily on the surface without looking beneath it, The Age of Innocence rewards us for the attention that we give it. And it does so without losing any of the emotional power of the story about the violence that we still commit every day. We just don’t talk about it so openly anymore. Of Martin Scorsese’s films, I currently consider this one to be his best. 90%

After Hours (1985)

When waking up late at night from the restless sleep of an office rat, Paul has to constantly tell himself that in a few days he will laugh about whatever bad things happen to him, but he can never be entirely sure about that. And thanks to Scorsese’s fondness for the dark corners of cities and of the human psyche, viewers can’t be too sure either. The unsteady transition from comedy to thriller and back is ensured by very steady directing and a well-written screenplay, sooner or later eliminating any doubts about the gratuitousness of any offshoot motif. Everything fits together beautifully, everything is interrelated and it all ends with an amazing office dance scene, an affirmation that, in this case, it was nothing grand, essential or groundbreaking. Just a bit of a filmmaking lark. With the highest level of craftsmanship. Appendix: Another item on the very long list of films that Timur Bekmambetov took inspiration from when putting Wanted together. 80%

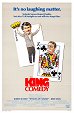

The King of Comedy (1982)

Pumpkin? Pipkin? Putkin? Papkin? Rupert Pupkin. A man who wants to be famous. A comical character that induces chills. Scorsese’s first excursion into the comedy genre ends before it gets to the comedy. It can only look at life in the shadow of American show business with an unsettling satirical distance and actually takes comedy as seriously as Pupkin does. On the other hand, Pupkin’s main handicap consists in a lack of distance and the inability to view his own behaviour from the outside. He is two absorbed in his role and perceives all of reality as a television show of which he is naturally the focal point. After Pupkin begins to drag others into his bubble, the situation is escalated almost to the point of becoming a crime drama, but still with an extraordinary feel for good old slapstick (whose style will be appreciated especially by fans of Jerry Lewis). The unpredictability of Pupkin’s behaviour thus switches from serving the purposes of comedy to serving the purposes of the thriller genre, thus giving rise to suspense instead of humour. The two genres blend together during Pupkin’s royal evening – his comedy performance is actually a recasting of very traumatic childhood experiences into a more appealing form (Jake La Motta’s stand-up routines in Raging Bull serve a similar therapeutic purpose). Did Scorsese intend to tell us that that the whole television industry is based on the same thing, i.e. hiding the serious behind the farcical? Or was he drawn primarily to the story of a man who so badly wants to get on the list that it ultimately doesn’t matter to him he is forever listed as a nutcase? A man who defines himself through stars and thus loses his own identity? I would seek the answers more deeply beneath the surface than in films that don’t turn fun into a science. 85%

Splendor (1989)

A film fully devoted to other films. Like Giuseppe Tornatore in Cinema Paradiso shortly before him, at the end of the 1980s Ettore Scola longed to sincerely thank cinema for simply existing. He handled the difficult task of depicting the idea of moving pictures with simple content and a complex form. A large part of this film built around the history of a particular small Italian cinema comprises excerpts from famous works of Italian and world cinema (all prints are dubbed in Italian in a somewhat non-cinephilic way) and subsequent discussions about them. What’s most probably required from us is mainly knowledge of the cited films and subsequent appreciation of how aptly they provide commentary on Italy’s political development and the aesthetic transformations of cinema. Due to the fragmented nature of the narrative, it is difficult to form an emotional bond with any of the three main characters. None of the scenes last long enough and we rarely see any continuous flow in the plot. Instead, we see fragments of memories. Sometimes in black-and-white, sometimes in colour. Like the films recalled here, which what is actually experienced is not only bound to, but sometimes merges with, most strikingly in the theatrically moving ending. Audiences come and go, films remain. It’s an idea that Splendor thoroughly fleshes out like few other films, though at the cost of significantly overlooking its characters. At the same time, it is an idea that will enthuse true film lovers, though others probably won’t find it compelling enough for a feature-length film. 75%