Reviews (935)

Zootopia (2016)

Zootopia cleverly combines the narrative formula of a cop movie about a rookie learning the ropes, a (neo-)noir crime film and socio-political satire. The individual levels are integral to each other and it doesn’t happen that, for example, a case is closed after an hour and a new story begins. It remains necessary to find out why the animals reverted to a feral state, which is why Judy has to return to her hometown for inspiration. There, thanks to the reformed Gideon, she discovers that the treacherousness of some animals is not connected with their origin, but with their nature. The action scenes also have a deeper dramaturgical foundation, taking as an example the Little Rodentia chase scene, during which Judy pursues a thief, who later helps her track down who is behind everything, and also saves the life of the mob boss’s daughter, who later plays her own role. Shortly before the end, Judy can use her acting skills, a demonstration of which we first saw in the opening scene, which leads to an elegant conclusion. It is a joy to see how the filmmakers took care to ensure that the individual components of the narrative worked together and that no motifs seemed incidental. In addition to its textbook conciseness, the film is also delightful with its references to The Godfather and Mission: Impossible (chase on/in a train) and intelligent humour (the now almost cult scene with sloths), which requires a bit more attention and patience from the viewer than other animated studio films. An added bonus that elevates this solid animated multi-genre feature to the level of one of the best American films of recent years is the sensitively composed message (very topical yet universal) about the equality of all animals, the consequences of prejudice, the drawbacks of dishonest political gamesmanship and the risks associated with speaking recklessly. Though the film does not criticise the police – on the contrary, it uses the militarisation of the police for one of the final gags – it points out that those who have great power and great influence on public opinion should choose their words especially carefully. Zootopia may not offer as elaborate a world as some Pixar films or the abundance of straightforward entertainment provided by Madagascar 3, but emotionally, narratively and intellectually, it is the pinnacle of contemporary animation and (perhaps) a future Disney classic. 90%

Robin Williams: Weapons of Self Destruction (2009) (shows)

Hall of Fame stand-up. Despite references to the political situation at the time (“Tony Blair and W. were like the United Nations production of Rainman”), Williams’s observations are timeless and, thanks to his God-given acting/improvisational talent, are incredibly funny, regardless of whether they accurately describe what’s wrong in society (“We didn't have Twitter. We had shitter. That was my chat room. We had useless conversations. We just didn’t fucking share them with the world…”) or address more mundane concerns of everyday life (the unforgettable bit on the topic of “where babies come from”). For a 58-year-old comedian who’d had a heart valve replaced (also the subject of humour) shortly before his performance, Williams has more energy than a ferret on meth. He constantly runs around the stage, furiously jumping from topic to topic (which is a pity, because when he talks about something at greater length, the punchline is more epic), he reacts quickly to the stimuli from the audience and rattles off one joke after another without missing a beat, while it seems that he hadn’t prepared much in advance for what he was going to talk about. With a similar cadence, the varying level of jokes doesn’t matter (parodying of gays, national stereotypes and occasional flashes of misogyny crop up), most of which will stick in your memory thanks to their masterful delivery, during which Williams fully engages his physical talent and various alterations of his voice (women’s gymnastics). Like few other stand-up comedians, he was able to tell jokes with his whole body. It’s a shame about what happened to him.

The Nurtull Gang (1923)

The roles of protagonist and narrator are played by a single woman who is exhausted from taking care of her son and not being able to even buy winter clothes with her salary, as well as from her monotonous job as a clerk, where she is harassed by her importunate boss (the mass scenes of urban commotion and the hustle and bustle of the mechanised office are reminiscent of King Vidor’s The Crowd shot five years later). She finds solace in a gang made up of her three female friends. Together they rent an apartment in Stockholm, where they dance, sing, drink beer and organise a strike for more respectable pay... The “chatty” retrospective narrative in first person rather strikingly reveals that the work on which the film is based was a serialised novel (written by Elin Wägner, journalist, writer, feminist and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences). By placing the characters in various situations and spaces, director Per Lindberg is able to evoke an atmosphere of closeness and solidarity between the women without using intertitles and in other scenes he skilfully depicts the changing power dynamics, which depend on one’s job, gender or class status. Mainly, it is a joy to see a film from almost a century ago that tells a story of relationships in a social context and celebrates the power of sisterhood. 75%

Germany in Autumn (1978)

Sixteen years after Oberhausen, the post-war generation of West German filmmakers composed another manifesto, this time in the form of a film. They expressed their opinions on the events of the so-called “German Autumn” (the name was derived ex post from their film), which began with the abduction of industrialist and former SS high official Hanns Martin-Schleyer and ended with the unexplained deaths of founding members of the Red Army Faction. The filmmakers take a collective approach to voicing their political position, as their individual statements converge into a single flow of information, and only thorough familiarity with the work of those involved will help you to distinguish who had a significant share in which segment. Immediate reflections on the ongoing political events are supplemented with philosophical consideration, with the theme of violence and its legitimacy serving as a frame of reference. With respect to the historical context, the state’s arrogation of the patent on violent activity raises concerns about the abuse of the apparatus of repression against citizens. Therefore, footage from Nazi weekly newsreels is “contextualised” and thus linked to contemporary events. The quote “When horror reaches a certain point, it doesn’t matter who commits it. Just so long as it comes to an end” crops up twice in the film. You will probably perceive it in a different light at the end than you did at the beginning. 75%

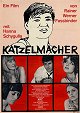

Katzelmacher (1969)

A few settings without buildings that would attract attention. A static camera. Only occasional use of direct causality. Shots ending with the simple exit of one or more characters from the frame (thus creating the impression that their hollow existence is limited to being in the picture – they do not exist outside of it). For Fassbinder, this radical rejection of the aesthetics of narrative film is not an end in itself. Formal economy serves the content – a cold look at the icy nature of the German middle class. The director is just as merciless towards his rootless peers as he is towards the married couple whose communication is progressively degraded to the point of comprising curt messages and violent physical outbursts. Fassbinder draws attention to the aggression and prejudices behind the laxly constructed façade with such matter-of-factness that the film verges on absurd comedy. It is also obvious from the absence of gradation that this wait for Godot will never end because of the attitude of the characters, whose inability to get on with their own lives culminates in herd aggression. 85%

So Long, My Son (2019)

With its long runtime and thoroughly developed characters, So Long, My Son is a sweeping yet detailed family fresco into which politics intrudes inconspicuously but with devastating consequences. Despite the seemingly apolitical focus on family relationships, Wang thus continues to critically examine previously taboo topics and the impacts of the decisions taken by the powerful on the lives of Chinese people past and present. It thus exhibits the main characteristics of the works of the so-called "sixth generation" of Chinese filmmakers, among which it ranks. ___ Wang does not serve up a linear narrative, which makes it difficult for us to access the characters’ feelings. He composes the portraits of the two families and their times from non-chronologically arranged fragments. The death of a son is the centrepiece of the narrative, to which the film directly or implicitly returns several times as if to an obsessive thought, thus enriching it with new layers. We repeatedly receive information necessary for the contextualisation of events only ex post from the dialogue or staging, costumes and colour palettes that are specific for the given period. However, the director’s restrained communicativeness does not serve to keep us busy putting together a complex narrative puzzle. Wang’s narrative is intuitive rather than architectural. He does not in any way telegraph flashbacks and flashforwards, as they are not clearly separate segments even for the characters, who always carry their past selves inside themselves. The complex structure, where the narrative repeatedly shifts backwards, the slower pace and the longer reverberation of shots also draw our attention to the motifs of memory, temporality and mortality. The protagonists want to seize, stop and reverse the flow of time. But they cannot “resolve” the past. The last hour of the film, which takes place in only one time plane, is extraordinarily intense thanks to the fact that the narrative finally "settles down". ___ Unlike classic melodramas, So Long, My Son does not express misery by aestheticizing it, but by taking a matter-of-fact and humble approach to it, with the camera always positioned so that the characters’ emotions are not exploited and something remains hidden. 80%

The Irishman (2019)

When, after roughly two hours, The Irishman stops switching between the two narrative lines and three different time planes that together set the film’s rhythm, it becomes clear that the wedding was not actually the primary destination of Frank’s journey. At the same time, one important character from Frank’s past comes into the road-movie framework. Contrary to the custom of accelerating the pace as the end approaches, the film slows down and becomes more focused, no longer engaging in a series of diversions and jumping between numerous people and events. We realise that the memory of a given event is of fundamental importance for Frank and he wants to recount it in as much detail as possible, step by step, minute by minute. Thanks to the context provided by the previous two hours, we concurrently comprehend what this is leading to and what the individual characters are experiencing. We start to understand that Frank had merely been carrying out another one of his missions, which usually ends with a house getting painted. ___ In the first narrative line, Frank is in the final phase of his life, just before his death. In the other, he is heading toward death. It seems that all of the events in his life involve death and dying in some way. The detached approach to killing well demonstrates Scorsese’s departure from the more dynamic style of his earlier mafia films. In The Irishman, violence is not “cool”; sometimes we don’t even see it, we only hear it from a distance. If an upbeat song is playing in the car during one of the murders, that is only because the driver turned on the radio to drown out the death rattle of the strangled victim. ___ Frank's blackened conscience, a reminder of his sins and the incompatibility of violent behaviour with the feeling of having a safe home, is represented by his daughter Peggy, thanks to whom we realise that Frank fills his emotional emptiness with words and diverts attention from his inner self to the outside. Though Frank’s relationship with his daughter may seem to be of secondary importance in the context of a story in which people die, cars explode and mobsters bribe top politicians, it is that relationship which best describes how Frank feels and what he longs for above all else: to go out into the world reconciled with himself and with his loved ones. Despite first appearances, the core of the film thus does not represent Frank’s involvement in the structures of the Italian-American mafia and trade unions, but what he lost due to his career advancement. Civil dialogue and time spent in the family circle appear to be more important than a detailed description of the underworld and a factual depiction of Frank’s work processes. Rather than an epic mafia saga, The Irishman is primarily an intimate drama about dysfunctional relationships and the constant presence of death, the basis of which we always carry within ourselves (as we realise thanks also to digitally rejuvenated acting veterans). 95%

Parasite (2019)

In dealing with popular genres, Parasite is more perfidious than the crime film Memories of Murder, the monster movie The Host and the postapocalyptic sci-fi flick Snowpiercer. Its narrative is not pieced together by conventions of a single genre that Bong would modify or refuse to comply with. Rather, it changes solely based on how the characters see and react to certain situations. Unlike in ordinary genre films, evil is not concentrated in a particular monster or villain, but manifests itself in the actions to which the protagonists resort in an effort to gain and maintain a certain social status. Predatory capitalism is the real antagonist. In the film, it is an invisible force that strengthens people’s desire to live someone else’s life. ___ The entire plot is derived from a particular social reality and the relationships between members of various classes of society, who are trying to game the system or defend the positions that they have achieved. Due to the rules that have been put in place, however, it is not possible to do either fairly. Reaching the top requires self-denial and crossing numerous boundaries. Disrespecting and breaching those boundaries comprise the dominant formal strategy and the film’s central metaphor. The rich live thanks to the hard work, blood and sweat of the poor, while the poor parasitise those who live in even deeper poverty in order to scratch out a living. They simultaneously need and hate each other. The space of clearly defined boundaries, the crossing of which will have unfortunate consequences, is an expansive modern house which from the outside represents a dream space for the protagonists. Its location on a hill contrasts with the central quartet’s modest home crouching below street level. Although the claustrophobically cramped interiors contribute to the fact that the destitute family sticks together more, they offer incomparably less comfort than the spacious rooms of the villa, whose inhabitants are spatially and emotionally more distant. ___ Though Parasite verges on farse through most of its runtime, in the end we perceive most of the characters rather as tragic victims of social stratification and economic injustice. The protagonists’ successes no longer bring comic catharsis, but vacillation as to whether the denial of one’s own individuality can be legitimised by the effort to maintain one’s position in the system. Amusement alternates with worries, compassion and a sense of injustice. Bong achieves this by altering the rhythm of the narrative and through skilful changes of perspective that redirect our sympathies. In the end, the tones of the individual characters’ stories are so incompatible that a reversal occurs and instead of a mere game of conquering the Wild West, there is a real and bloody breaking down of the boundaries between fiction and reality, civilisation and wilderness. The film involves not only a clash of different classes and ways of relating to the world, but also a blending of horror, black comedy and melodrama. The mastery with which Bong combines these seemingly incongruent elements into a consistently entertaining whole, in which every cut and movement of the camera is calculated with Hitchcockian precision, offers the most convincing argument against doubts as to whether a similarly “viewer-friendly” film deserved the Palme d’Or at Cannes. 90%

Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

Just as Raging Bull probably didn’t fill many with enthusiasm for boxing or The Aviator for flying, Bringing Out the Dead won’t swell the ranks of people interested in medicine. Scorsese shows the saving of lives in all its squalidness. After the aesthetically refined, nearly bloodless Kundun, he probably needed to get his hands a little bit dirty again. Frank doesn’t have much time to think about why he is doing this disgusting and thankless job, but he feels that he can't have a fulfilling life with anything else. Like a shark that can’t stop moving, like an untreated addict who needs a steady supply of adrenaline, he navigates through night-time New York three times, accompanied by three different partners whose behaviour reflects Frank’s confused train of thought (from rapprochement to the desire to kill some patients). Relatively monotonous in his expressions, Cage was the perfect choice for the role, as most of his states, whether excited or totally lethargic, are expressed by other characters, sharp cuts, gliding camera movements and eye-catching lighting (due to overexposed scenes, characters dressed in light-coloured clothing look like ghosts in the dark). If the film is reminiscent of a psychedelic rock music video in places, it is not (for the most part) a matter of the director, editor or cameraman running wild, but rather a way to present to us the protagonist's precipitous perception of what’s going on around him without long bits of soul-searching dialogue. Frank’s returns to his messy apartment are too brief for him to replenish his energy. He’s always on the move. He runs away from the feelings of guilt that took on the form of an eighteen-year-old girl. He runs away from death, whose inevitability he is reminded of on a daily basis, in spite of which he refuses to reconcile himself with it. He tries to find absolution and solace in Mary (the Madonna), to whom he finds his way only after he relieves her father of his earthly suffering and replaces him through his actions. On a more general level, Bringing Out the Dead is a variation of the eternal story of the conflict between false prophets and messengers of the end of the world with a handful of persistent individuals who, even at the cost of their own self-destruction, try to keep the world from becoming unbearable. The intoxicating possibility of being God for a moment is stronger than the awareness of the inevitability of the end and the impossibility of changing the course of things (the recurring situations with Noel or Mr. Oh). Once a saviour, always a saviour. You won’t find a better drug on the streets. Like Frank, we are also overwhelmed by the rapid verbal exchanges, ambiguous images, the roar of the streets and loud music (which completes the acid-trip atmosphere while commenting on what’s happening). Thanks to the constant supply of audio-visual material, our minds are kept busy and the film goes by devilishly fast, leaving us astonished by the strangeness we have just witnessed over the past two hours (did a white horse really appear in that one shot?). Bring Out the Dead offers variations on some situations in Taxi Driver, but it is not merely an addendum to the latter film. The protagonist no longer stands opposite the despised creatures of the night. He has no choice but to live with them. Though he understands that fighting doesn’t make sense, he doesn’t stop trying. Pure Scorsese. 80%

Ad Astra (2019)

Gray further develops the theme of dysfunctional communication between immediate family members. They are unable to establish a dialogue because they escape into their own individual worlds and stay in their usual models of existence. Though Gray remains thematically and stylistically consistent, his view is more ambitious from film to film, while the protagonists’ ambitions grow accordingly. The distance that they had to overcome in an effort to find common ground was previously insurmountable only in a figurative sense. In Ad Astra, the distances between the protagonists are literally astronomical. This brought about a reinforcement of the main idea of Gray’s filmography – regardless of how far we roam, a place that gives meaning to our existence will always be in reach. ___ Recurring reservations about Gray’s latest work have a paradoxical nature. Critics admonish the film for not eliciting a stronger emotional response because of its monotonousness and ponderousness, while also saying that it is too literal, too obviously predictable and banal in its message. It’s as if they couldn’t see that the tension between the emotional distance on the one hand and the effort to share as much as possible on the other hand is the driving force of the film as well as its crucial distinguishing element. This duality is reflected as early as in the introductory action scene. The impression of vertigo evoked by the sight of a falling body and the POV shots contrasts with the icy calm of McBride, who matter-of-factly informs his commanders how he intends to handle the situation. The fact that he reacts to a lethally hazardous situation as if he has nothing to lose offers a relatively precise image of the main protagonist. ___ The uncertainty under whose influence the protagonist deviates from the mission’s objective is initially reflected in the words, actions and facial expressions of the supporting characters and later in Roy’s voiceover. The spectacular expedition to obtain knowledge gradually transforms into intimate family therapy. The film increasingly shifts from action to introspection, from broad strokes to details. This stylistic development corresponds to the growing scepticism with which Ad Astra frames heroic deeds. Acts of heroism performed only to satisfy one’s own ego or as a means of avoiding seemingly banal relationship commitments are, from the film’s viewpoint, a path to loneliness and social isolation. During the protagonist’s odyssey, people and animals die for no reason and, in the end, the main benefit of Roy’s mission is not finding the lost patriarch. He must go through this in order to reveal the reality concealed behind the myth that has been created around his father. ___ Roy uses an idealised image of himself based on his father’s upbringing as a shield against reality. Therefore, it is important that we have access to his concept of himself and can see or, as the case may be, hear how he gradually becomes disturbed by facts that do not correspond to the mythologised image of his father. Due to the pathological introversion of the protagonist, Gray decided to use a voiceover, which reflects Roy’s feelings in the present tense, not retrospectively, and thus continuously takes his character development into account. However, Roy’s detached tone of voice and the lack of passion in the sentences he utters do not primarily indicate strict work discipline, but rather his emotionally anesthetised state. He is incapable of openly communicating with others and talks to himself as if to the computer terminal in front of which he has to undergo regular psychological evaluations. He is inspected both internally and externally. ___ A certain warmth is present only in brief flashes of memories of his mother and former partner, for whom Roy was never fully present because he clung too tightly to his father’s legacy. Also, when questioned about his father’s disappearance during a work briefing, he symptomatically recalls not how he reacted to the event, but how his mother reacted. The fleeting presence of women in the narrative is legitimised by the filtering of all events through the perspective of a man who is unable to connect with his own emotions, let alone those of his loved ones. Roy mistakenly seeks understanding from his father, whom he admires for his career successes. In Roy’s voice-over, the two men merge from the beginning, when he derives his own worth from doing his own job well. However, the person who anchors him in the present, who defines the beginning and end of his story, is a woman, who represents his future, as she brings him back to life. ___ The way the film is constructed does not in fact needlessly double the message that it conveys. We do not hear offscreen what we see, but we see what Roy sees and perceives. Together with flashbacks, the parallel narration of various stories layers the seemingly straightforward monomyth about the protagonist’s journey, thus making it diverse and stimulating. The structure sets the text and the subtext against each other by maintaining distance from the hero and letting him comment on his changing position in the heroic narrative. Gray did not make a film that was spiritual or poetic, but one that is especially intellectual, particularly by revitalising the basic building blocks of adventure stories. Layer by layer, the film unmasks the heroic myth in order to show, based on the example of one flawed hero, how unstable the myth’s foundations are and thus it has to work on a different principle than that of traditional Hollywood genre movies, which merely recycle the myth. Ad Astra offers an emotionally powerful experience not in spite of its subdued nature, but precisely because of it. 90%