Reviews (838)

The Zone of Interest (2023)

Though throughout most of the film we don’t see anything other than an outwardly ordinary German family, the layered soundtrack, which mixes the chirping of birds and the murmur of a river with a constant mechanical drone, evokes an almost indefinable feeling from the first minutes, a feeling that something intimately familiar seems strange and oppressive. The resulting effect is best described by the term “unheimlich” from Freud’s psychoanalysis, i.e. uncanny. Zone of Interest is extremely disturbing in its ability to capture the abnormality of the everyday. ___ The unchanging, rigid apathy of the depicted world is underscored by predominantly static shots without artificial lighting and with great depth of field. The cameras are positioned in different corners of the house and garden like in a reality TV show. They record the movements of the actors without artistic stylisation, thus evoking an impression of the distant past. Not even the editing adheres to the principles of standard narrative cinema. The switching between cameras depends on which room a character has just entered. Everything thus seemingly takes place in the present tense. Subjectivity and creativity, or rather the possibility of averting one’s gaze and disrupting the order of things, are suppressed. The tasks that Höss carries out are mindless administrative work. Genocide is a logistical process. ___ If we wanted to locate the source of the tension that pervades the whole film, it would be the clash between what the Hösses are willing to see and what happens outside of their house and garden. Glazer’s distinct style is a form of rejection. He consistently avoids aestheticizing one of the greatest tragedies of modern history. At the same time, he succeeds in using empty space in a way that is far more powerful than direct depiction. Because we cannot see the other side, we are aware of what is happening there. Our effort to fill this gap leads to the fact that we cannot stop thinking about the ongoing violence. ___ Glazer also included night scenes shot with a special thermal camera. This involves a reconstruction of the story of a ninety-year-old Polish woman named Alexandra, whom Glazer met during his research. She became for him a symbol of resistance, a light in the darkness. Taking into account the perspective of those who actively resisted Nazism is one of the few elements that Zone of Interest shares with more conventional dramas about the Holocaust. Where other Oscar-winning dramas offer catharsis and a reassurance that humanity will ultimately prevail, Zone of Interest offers only a disturbing presentiment of things to come. We see that the concentration camp has become a museum where cleaners mechanically vacuum the dust and polish the display cases. A single glance inside the death factory peculiarly does not reveal any atrocities. Rather, it is characterised by the same emotionless routine that we saw in the Hösses’ bourgeois household. We have become accustomed to the presence of the Holocaust in our collective memory and in the media space. Zone of Interest shines a light on the mundanity, banality and elusiveness of the evil to which we contribute merely by remaining indifferent. 90%

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One (2023)

More graphically than the previous instalments of the M:I franchise, Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One raises concerns associated with the future of humanity and of Hollywood. The film, whose main villain is an extraordinarily powerful artificial intelligence, was released to cinemas during the dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers, who in addition to fair compensation also demanded a guarantee that they would not be replaced by modern technologies. The computer-generated illusions in the film threaten the approach to truth and relativise the ethical categories of good and evil. Ethan Hunt/Tom Cruise is naturally the only safeguard against machines taking over the world, the last link holding human society together (this is literally true in the final action scene, when his partner uses him as a ladder). What awaits him is a confrontation with the most powerful adversary he has faced yet, which collects our best-hidden secrets, reshapes reality and is everywhere and nowhere. In other words, he will have to take on a (false) god, whose interests are represented by a villain with the biblical name of Gabriel, and the key to controlling it is in the shape of a cross. ___ Though few people in Hollywood today are able to so effectively evoke the dizzying feeling of forward motion as a running Tom Cruise, Dead Reckoning is to a significant extent a film of reversions, to the old faces and analogue technology of the Cold War period, to the protagonist’s past and to the skewed angles of De Palma’s paranoid first Mission: Impossible. And even deeper into the past. To The General, Hitchcock’s comedy spy thrillers and related 1970s caper comedies like What’s Up, Doc? McQuarrie combines the structural principles of the cinema of attractions and classic Hollywood, but he intensifies the situations and takes them to such an extreme that even the characters sometimes laugh resignedly over their impossibility. Tension arises between the (unseen) classic and (self-reflexive) post-modern approach to style and narrative when the film alternately fulfils and defies our expectations, as it is playfully ironic at times and tragically romantic at other time. Similarly to the way Hunt defies the algorithm and how the protagonists are aided by disguises and advanced surveillance technologies, which fail repeatedly, however. In the end, they can rely only on human bodies, ingenuity and teamwork. ___ The characters’ distrust and suspicion toward what they see and hear is expressed in the dialogue scenes by the tilted camera shooting from up close and in decentred compositions of the actors’ faces. Sometimes without establishing shots, which, together with the hasty editing (including cross-axis jumps), intensifies the feeling of disorientation and the impossibility of determining what is true and who is running the show. At other times, usually while the next course of action is being planned, the camera uneasily circles the characters. Thanks to this, even the chatty explanatory sequences are thrilling and there are practically no statics moment in the film. The almost cubist composition of the picture occurs roughly at the midpoint of the narrative during the meeting of most of the key players at a party at Doge’s Palace in Venice. The characters’ dialogue as they try to figure out their adversaries’ motivations is edited in the rhythm of the diegetic background music. Their verbal shootout is reminiscent of a dance performance, as every camera movement is synchronized with the soundtrack. Also in other scenes, though not as conspicuously, the information conveyed is of comparable importance as the aesthetic pleasure of the interplay of shapes and lines. For example, during the chase through the narrow and dark streets and canals of Venice, the order of shots is not determined only by the continuity of the ongoing action, but also by the rhythmic alternation of contrasting and complementary angles and movements. ___ The episodically structured film traditionally comprises several massive action sequences, each of which having its own objective, obstacles and course of development. At the same time, they are firmly interlinked. Each one prepares us for what will happen next (which doesn’t always go according to the presented plan) and sets in motion another notional cog in the flawlessly tuned mechanism. The chosen locations also complement each other, as they give the characters less and less room to manoeuvre (from an expansive multi-level airport to a closed train). Almost every sequence works with a tight deadline and the necessity of precise timing, both across the given sequence and in its constituent parts (for example, the necessity of escaping from the car before it gets destroyed by an oncoming metro train at the end of the Rome sequence). ___ Unlike in blockbuster comic book adaptations and the high-octane, progressively dumber Fast & Furious movies, the human element is never overshadowed by the shootouts and explosions in Dead Reckoning. On the contrary, they are doubly suspenseful thanks to the chemistry between the believable characters. Their characterisation, which is carried out without pauses in the action or during their preparations for the next task, is skilfully connected with certain recurring motifs and props (e.g. Hunt’s lighter, the passing around of which among the characters reflects the development of the relationship between Grace and the protagonist). That’s what the franchise is about, as Cruise doesn’t hesitate to risk his own life again and again with maniacal determination in order to convince us that an intelligent machine can never do anything as spectacular as a human (or a team of humans) can do. In the latest instalment of the M:I franchise, which is the most narratively harmonious and stylistically experimental of the lot, he does this for the first time not only in the subtext, but in the foreground. The time for subtlety has passed. 95%

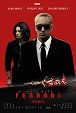

Ferrari (2023)

Enzo Ferrari teaches his son that when things work well, they are pleasing to the eye. Michael Mann follows the same maxim. Ferrari, another of his portraits of an obstinate professional in an existential crisis, is a joy to watch thanks to its narrative cohesiveness and the fact that it rhythmically fires on all cylinders. During practically every shot in the exposition, we learn some important information that will be put to good use later in the film. At the same time, the exposition introduces the governing stylistic technique consisting in the use of duality and contrasts (e.g. light scenes with Enzo’s mistress vs. dark scenes with his wife). Slower scenes regularly alternate with faster ones, movement alternates with motionlessness and the melodramatic (and utterly operatic in one scene) exaggeration of certain emotions, particularly sorrow, which both spouses deal with, each in their own way. Mann follows the example of classic Hollywood directors like Hawks and Sirk and lets the mise-en-scéne tell much more of the story than other contemporary directors would allow. At the same time, he defies the conventions of classic biographical dramas as he focuses only on a brief period of Ferrari’s life and, instead of creating artificial conflicts, he superbly dramatises everyday encounters and ordinary business operations (paying wages, signing documents, concluding agreements with investors). This feel for detail also contributes to the believability of the fictional world. Ferrari’s work always clashes – either constructively or destructively – with his personal life (Ferrari finds common ground with his son thanks to his work, but he also loses his wife because of it). The lion’s share of emotion and excitement is typically found in the cinematically brilliant scenes of races, which represent Ferrari’s greatest passion. Unlike other sports movies, however, such scenes do not bring catharsis, but rather recall the fragility of life (thanks in part to the excellent sound design, the race cars of the time really do not seem safe) and recognition of the fact that however hard you try to have everything under control, certain events cannot be foreseen and you ultimately have no choice but to accept them and somehow incorporate them into your life story. 90%

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Martin Scorsese and Eric Roth have taken a muddled, mediocre book and turned it into a great American novel in film form. Killers of the Flower Moon is a monumental, multi-voiced and timeless chronicle of the fall of a community whose lust for wealth is stronger than love, even though its members are aware that they are preparing the next generation for the future through their own behaviour. The film is dark and slow and feels longer than The Irishman, for example, but that length is justified, as it makes it possible for us to gradually get into that community and see at first hand how greed and cynicism gradually and inevitably spread to the country, become entrenched and consume the characters. Throughout the film, we find ourselves in close proximity to a confident and seemingly all-powerful, yet essentially banal and sometimes comically obtuse evil whose proper punishment seems rather unlikely, which is exactly as frustrating and exhausting as Scorsese most likely intended it to be. By comparison, the voice of goodness is weakened by sickness and the “medicine” administered, and it is limited to naming the one who died (which is something of a Scorsese trademark). Despite that – and thanks to the dignity that Lily Gladstone radiates – it has a central, evidentiary role in the narrative. Killers is primarily an indictment of the murderers whose existence should ideally have been erased from American history (because many still profit from their crimes to this day) and an emphatic demand to give back a sense of humanity to those whose lives were reduced to a few thousand dollars decades ago; the director’s closing cameo leaves us in no doubt about this. ___ Scorsese directs his lament with the surehandedness of a master. This time, he economises on the spectacular dolly and Steadicam shots, instead relying on the actors and Thelma Schoonmaker’s feel for rhythm. As a message about the substance of American capitalism, his plunge into the darkness could eventually become an equally essential work as Giant (1956), Once Upon a Time in the West, The Godfather and There Will Be Blood. At the same time, the intense hopelessness and the atmosphere of irreversible decline reminded me of Tárr’s films. No, that won’t come easy in the cinemas for this proof that you can still make your magnum opus in your seventies. 90%

Tony, Shelly and the Magic Light (2023)

Czech (and Slovak) animation has again risen to the world-class level in recent years. This has most recently been confirmed by the Czech-Slovak-Hungarian stop-motion film Tony, Shelly and the Magic Light, which received an award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival. Thanks to its amazing colours, lights (!) and original visual ideas, Filip Pošivač’s feature-length debut looks so good that I wanted to slowly pause every shot and savour it for a moment. In terms of its superb craftsmanship alone (for example, Denisa Buranová’s dynamic cinematography, which takes something from live-action filmmaking and contributes to the originality of the creative concept), this is an extraordinary film in which it never once seemed to me that the filmmakers made any compromises, let alone skimped on anything. And the story, written by Jana Šrámková, is also exceptional, not only in the domestic context, in the way that it is both comprehensible for children (judging from their reactions) and appealing to adults on a deeper level as it tells the story of the little big adventure of an eleven-year-old boy who glows. Since this film has quite a few thematic levels (depression, parenthood, self-realisation), you may find a different key to interpreting it, but for me the main thing was the unusually sensitive (and extremely relatable) narrative about the experience of a child who is neurodivergent (or simply different in some way) and – despite his loving, hyper-protective parents – tries to find his place in society, which is represented in the film by a single multi-storey apartment building. Based on the example of the titular duo, the film shows that it is quite beneficial to meet people or at least one person with whom you can identify (Tony is the only one who can see Shelly’s imaginings) and accept yourself in your own differentness to such a degree that you gain the courage to step outside of your own private (fantasy) world and to share with others your own inner light, which you had long seen as a limitation. Some have the good fortune to do that when they are eleven, some when they are twenty-nine. A beautiful film.

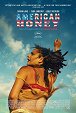

American Honey (2016)

The protagonist’s journey of self-discovery was covered in Andrea Arnold’s previous films, but in American Honey, it is written directly into the unconventional structure of the film for the first time and is manifested both by the choice of setting and the segmentation of the narrative by means of longer musical interludes, during which we enjoy the present moment with the protagonist and do not think about how the film (and the journey) will continue. Whereas Star’s inner liberation happens below the surface, the American landscape through which the protagonist and her companions travel undergoes a significant transformation. Through poetic shots of the setting sun and oil-field fires, we are – like Star – repeatedly pull out of the harsh reality of the lives of those who have who have nothing to lose, which is filmed with an unpleasant degree of detail. Unlike other female wanderers depicted in films, however, Star is not a defenceless figure preyed upon by men. She quickly masters the rules of market capitalism and begins to confidently offer what she has in order to get what she wants. Despite that, the matter-of-factness with which she repeatedly gets into strange men’s cars makes her nervous and raises within her the question of when she will pay for her trustingness. Though the expansive American plains across which the characters travel call for a widescreen picture, Arnold remains faithful to the narrowed academic format. Thanks to that, most of the shots are dominated by Sasha Lane, who also determines who and what we see. The pairing of the energetic protagonist with the movement of the camera gives the film an immediacy and liveliness that grow even stronger during the authentic erotic scenes and other moments when Star lets her instincts guide her. Despite its sensuousness, American Honey is also a merciless portrait of a country in which everything can be converted into a medium of exchange and where you can achieve your dream only if you sell yourself. 90%

Blonde (2022)

Blonde is an exceptional work for the same reasons many people hate it: its fragmentation, the excessive length of many scenes, the focus on the surface, the inconstant visual identity, the building of pressure without catharsis, it’s not an empathetic biopic but a pessimistic collection of horrors with a dissociated protagonist who wanders through her own subconscious – the whole film can be seen as her nightmare (also, the Badalamenti-esque soundtrack by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis is reminiscent of Lynch, who had prepared and ultimately shelved a film about Marilyn Monroe in the 1980s). The breaking down and decontextualisation of the myth and iconography of Marilyn Monroe work better in images than in Joyce Carol Oates’s graphomaniacal book on which the film is based (though the film uses the book’s narrative and storyline relatively consistently, its nihilism is closer to Ballard or Palahniuk). I understand that sexual violence, nervous breakdowns and ideas outside the boundaries of taste (a foetus talking to its mother) may be too much for some. I understand that not everyone will accept the concept of a film in which beauty is almost always associated with pain and sex with humiliation, a film that places the viewer in the extremely uncomfortable position of voyeuristic accomplice. However, I would expect critics to at least have the ability to distinguish between a real historical figure and a textual construct that serves a certain narrative or symbolic purpose, or rather between a misogynistic film and a film about misogyny (and the cruelty of the looks that strip a person of their identity and turns one into a projection screen for someone else’s fantasies). 90%

La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2000)

In its uncut version, Peter Watkins’s magnum opus lasts almost six hours, but I was never bored for even a minute. The English director reconstructs the brief, brutally suppressed Paris Commune government in the form of a sequence of television and radio reports directly from the scene (in the film Culloden, he similarly demonstrated what the Jacobite uprising might have looked like if television cameras had existed at that time). He proceeds on the basis of thoroughly researched historical sources, from which he also quotes extensively in the intertitles. This would have been a unique work thanks only to the (non-)actors committed to their roles (for example, members of the bourgeoisie are played by conservative party voters so that their contempt for the rebels is more authentic) and the long, fragmented shots that capture the chaos of the times while also being highly organised, but Watkins did not remain at the pseudo-documentary level. In the spirit of the Theatre of the Oppressed, the (non-)actors sometimes break the fourth wall and comment on the staged events from the perspective of their own time (1999), or rather reflect on how older and newer media contribute to the formulation of reality and the unequal distribution of power based on class and gender. The film thus also conveys communal ideas by constantly drawing attention to the fact that it is itself the work of a group of like-minded people who are striving for economic and social changes. At the same time, it is far more dynamic and less self-centred than, for example, Godard’s deconstructionist film essays of the 1960s and 1970s. Although the set is minimalist (the entire shoot took place over the course of two weeks in an abandoned factory on the outskirts of Paris), at the end I had the feeling that I had a relatively good grasp of the period and the problems that the Parisian working class was facing at the time, and I also understood why comprehending them is relevant for the present. I imagine that in an ideal world, students would leave every history lesson with the same feelings. 90%

West Side Story (2021)

After seeing West Side Story, it occurs to me that this is turning out to be a great year for musicals. Unlike Annette, which exhibits a clash of different poetics, West Side Story is, in its basic outlines, a pure musical melodrama about love that does not distinguish between good and evil; only its lack of an overture and intermission prevent it from being perfect. Spielberg and Kushner did not radically alter the timeless story of the multiple characters, who are prevented by violence, poverty and racism from fulfilling their dreams of building something of value on the ruins in which they live. Rather, they just fleshed out Tony’s past, added one important character (stylishly played by Rita Moreno), made the female characters stronger and more active, changed the order of certain songs, and made the motifs particularly relevant for the present day (racial violence, immigrants vs. white trash, tradition vs. foreign cultural influences). In comparison with the 1961 adaptation, the cast is more diverse (no whites playing Puerto Ricans, plus a lot of deliberately un-subtitled Spanish lines), as is the ensemble of characters (which include a trans boy). The actors, particularly Ariana DeBose as Anita, are fantastic, and the way Spielberg (or rather Kaminski) uses colour to differentiate the characters and bring clarity to the scenes in which several of them appear at once is admirable. Together with the specific lighting, choice of locations and camera movements, the colours also help to define the feuding sub-worlds, whose conflicts (whether physically, when the Jets and Sharks rumble at midnight, or in a parallel cut) are the emotional highlights of the film. And emotion is plentiful in West Side Story. The version from the 1960s, to which I returned a few days ago, is a nice colouring book and I watched it mostly with detached appreciation. Spielberg's treatment, which adroitly dances between the reality of the gritty New York streets and stylisation in the mould of classic Hollywood musicals, absolutely captivated me from the mambo in the school gym (which, like latter-day America, is a great, colourful celebration of life) and I just continued to be carried away, thrilled and moved by it. That’s not even to mention the clear arrangement of the dance scenes, the smooth tempo changes and the brilliant rhythmisation achieved through in-camera editing, which is not surprising for a director who also shoots action and comedy scenes as musical numbers. 90%

The Velvet Underground (2021)

Talking heads commenting in great detail on the subject and unique archival footage would be enough to make The Velvet Underground an information-packed two-hour documentary from which you will really learn a lot about the titular band and the American counterculture of the 1960s. Thanks to Haynes’s self-aware, avant-garde play with imagery, which has the vibe of both early Warhol and late Godard and is always subordinated to the divine music with rhythmic precision, The Velvet Underground is both an incredible audio-visual experience and one of the best films of the year.