Reviews (840)

Back to Black (2024)

Fifty Shades of Grey, but done a bit differently. Director Sam Taylor-Johnson and screenwriter Matt Greenhalgh could have used Amy Winehouse’s story to construct an emotional drama about fame, addiction, voyeurism and the excessive demands placed on how famous women are supposed to behave and look (mainly decently). Instead of that, they decided to take an absolutely dull, mediocre approach to telling a bittersweet fable about a girl unhappily in love, who wants to be a mother (which is her main desire and greatest vulnerability). Only a minimum of space is dedicated to the process of composing and recording music or to any effort to understand the deeper causes of Amy’s predisposition to addiction (no, I really don’t think it was because of a broken heart and the death of her grandmother). It’s as if the film wasn’t made for Amy and her fans. The main point of Back to Black seems to be to clear the name of the two men who opportunistically exploited the singer’s vulnerability and contributed to her tragic demise. Here they behave – at least toward the protagonist – in an exemplary manner with exaggerated concern (for comparison, watch the documentary from 2015). Even if we set aside the ethically questionable retouching of reality and laying blame on the victim and her impulsive behaviour, Back to Black remains a below average film that is unnecessary in every respect (including Marisa Abela’s performance, unfortunately). It gains depth and veracity only once, during the closing credits, which feature Nick Cave’s heartfelt performance of his ballad “Song for Amy”. 40%

Ferrari (2023)

Enzo Ferrari teaches his son that when things work well, they are pleasing to the eye. Michael Mann follows the same maxim. Ferrari, another of his portraits of an obstinate professional in an existential crisis, is a joy to watch thanks to its narrative cohesiveness and the fact that it rhythmically fires on all cylinders. During practically every shot in the exposition, we learn some important information that will be put to good use later in the film. At the same time, the exposition introduces the governing stylistic technique consisting in the use of duality and contrasts (e.g. light scenes with Enzo’s mistress vs. dark scenes with his wife). Slower scenes regularly alternate with faster ones, movement alternates with motionlessness and the melodramatic (and utterly operatic in one scene) exaggeration of certain emotions, particularly sorrow, which both spouses deal with, each in their own way. Mann follows the example of classic Hollywood directors like Hawks and Sirk and lets the mise-en-scéne tell much more of the story than other contemporary directors would allow. At the same time, he defies the conventions of classic biographical dramas as he focuses only on a brief period of Ferrari’s life and, instead of creating artificial conflicts, he superbly dramatises everyday encounters and ordinary business operations (paying wages, signing documents, concluding agreements with investors). This feel for detail also contributes to the believability of the fictional world. Ferrari’s work always clashes – either constructively or destructively – with his personal life (Ferrari finds common ground with his son thanks to his work, but he also loses his wife because of it). The lion’s share of emotion and excitement is typically found in the cinematically brilliant scenes of races, which represent Ferrari’s greatest passion. Unlike other sports movies, however, such scenes do not bring catharsis, but rather recall the fragility of life (thanks in part to the excellent sound design, the race cars of the time really do not seem safe) and recognition of the fact that however hard you try to have everything under control, certain events cannot be foreseen and you ultimately have no choice but to accept them and somehow incorporate them into your life story. 90%

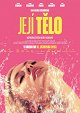

Her Body (2023)

Adam: Why are you hopping? Andrea: Why are you walking? This bit of dialogue essentially contains everything that we learn about Andrea Absolonová’s motivations over the course of (not quite) two hours. Her Body is thus an apt title. The film makes no effort to psychologise her (and it is more consistent in this respect than the recent Brothers). We see from up close what her body has been through in various phases of her life, but we do not get a look inside her head. The scene involving an interview with a journalist indicates that she just didn’t have much to say. In the context of biographical dramas that have the need to explain why someone did this and that, it is an original approach. But to what end? The inability to go in depth isn’t offset by the originality or intensity of the stylistic techniques. It is neither carnal nor hard enough for a body horror movie. The only unpleasant scene is the one in which Andrea is on her hands and knees after being injured and stretches her bruised body. Otherwise, the film is remarkably easy to watch. Even when the protagonist is lying in the hospital with a neck brace or with a brain tumour, she looks great (several times I recalled what Ebert said about “Ali MacGraw’s Disease”: a movie illness in which the only symptom is that the patient grows more beautiful until finally dying). In fact, the family scenes with her father and mother are painful, though only because of their theatrical stiffness and unbelievability, when I had the feeling that I was watching several strangers (who conspicuously do not age with the passage of time) pretending to be blood relatives. We learn very little about the workings of the porn industry at the turn of the millennium. The story is cut down to basic events. There is no context (the motif of working with one’s body as a tool could have been made more multi-dimensional by emphasising the obsession with performance and success that became normalised in the 1990s). Andrea simply just has sex with various porn actors. She doesn’t deal with anything else around her. She doesn’t have to. Everyone is extremely kind and understanding. It’s nice that the film doesn’t take a moralistic stance toward porn (unlike, for example, the Swedish film Pleasure, which didn’t take a stance toward anything due to its cautious approach to the lives of actual people). It’s simply another physical activity at which the ambitious protagonist wants to be the best…which is simplistically emphasised by Adam’s line “you’re not in a competition here” (and there are plenty of similarly superfluous, leading statements). But what else? The problem with the film is not that it doesn’t go to any great lengths to explain what we see, but that it simply has nothing to explain. It’s hollow, it’s neither entertaining nor moving, and it doesn’t create dramatic tension. It does not have a clear theme or point of view (a problem of dramaturgy). It merely reconstructs a few loosely connected episodes from Absolonová’s life without offering anything that would be surprising. She was an excellent diver, then she got injured, then she became a famous porn actress without making any visible effort and then died young. She had a close relationship only with her younger sister, but in a film teetering between docudrama and family melodrama, this motif is just as feeble and poorly developed as all of the others (e.g. the eating disorder). There is no added drama or emotion, no deeper reflection on anything. Just her (still attractive) body. 50%

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Martin Scorsese and Eric Roth have taken a muddled, mediocre book and turned it into a great American novel in film form. Killers of the Flower Moon is a monumental, multi-voiced and timeless chronicle of the fall of a community whose lust for wealth is stronger than love, even though its members are aware that they are preparing the next generation for the future through their own behaviour. The film is dark and slow and feels longer than The Irishman, for example, but that length is justified, as it makes it possible for us to gradually get into that community and see at first hand how greed and cynicism gradually and inevitably spread to the country, become entrenched and consume the characters. Throughout the film, we find ourselves in close proximity to a confident and seemingly all-powerful, yet essentially banal and sometimes comically obtuse evil whose proper punishment seems rather unlikely, which is exactly as frustrating and exhausting as Scorsese most likely intended it to be. By comparison, the voice of goodness is weakened by sickness and the “medicine” administered, and it is limited to naming the one who died (which is something of a Scorsese trademark). Despite that – and thanks to the dignity that Lily Gladstone radiates – it has a central, evidentiary role in the narrative. Killers is primarily an indictment of the murderers whose existence should ideally have been erased from American history (because many still profit from their crimes to this day) and an emphatic demand to give back a sense of humanity to those whose lives were reduced to a few thousand dollars decades ago; the director’s closing cameo leaves us in no doubt about this. ___ Scorsese directs his lament with the surehandedness of a master. This time, he economises on the spectacular dolly and Steadicam shots, instead relying on the actors and Thelma Schoonmaker’s feel for rhythm. As a message about the substance of American capitalism, his plunge into the darkness could eventually become an equally essential work as Giant (1956), Once Upon a Time in the West, The Godfather and There Will Be Blood. At the same time, the intense hopelessness and the atmosphere of irreversible decline reminded me of Tárr’s films. No, that won’t come easy in the cinemas for this proof that you can still make your magnum opus in your seventies. 90%

Magic Mike's Last Dance (2023)

The first Magic Mike was an uncomplicated social drama, the second a road movie and this, the third one, is a Lubitsch-esque conversational comedy built on the foundation of a backstage musical. Or Pretty Woman in reverse, if you like (a rich housewife buys the company of a stripper with a heart of gold, and the question of “love or money?” stands at the centre of the story). However, there is also criticism of the capitalism/patriarchy that turns everything into a commodity (London is humorously presented through a series of shots of souvenirs) and promises to women, who are at the centre of the narrative for the first time, freedom (the perhaps most expensive shop in the city is aptly called Liberty) and fulfilment of their most secret fantasies, but only if they give up their wealth and power. In other words, it really has to be a fantasy realised somewhere in the theatre, without any overlap with the real world, where men still make the decisions. Magic Mike’s Last Dance can also be seen as Soderbergh’s effort to subversively play around with the concept of legacy sequels, at which he both succeeds and fails (and reflects his own position, when, like Mike, he has to build on a successful brand, sell himself and rely on patrons instead of building something new because of the systemic conditions). The protagonist wouldn’t have done anything spectacular without someone else’s money and a job offer; he simply would have continued to make a living as a bartender and remained a lone wolf. The old gang only appears briefly during a Zoom call and there are minimal references to the preceding instalments (a flashback with a striptease in a police costume). The dance scenes, thanks to which this is one of the most erotic Hollywood films without sex (and it will make your nipples erect regardless of your gender or orientation) are parodically overwrought (the opening “pornographic” dance à la Fifty Shades of Grey and its moist variation at the end). The deliberate formulaicness with the division of the story into basic archetypes is made visible by the straightforward voiceover, which transform’s Mike’s return to the stage almost into a fairy tale or mythical story. It’s definitely not as silly and shallow as it may seem when viewing it on a superficial level. 75%

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One (2023)

More graphically than the previous instalments of the M:I franchise, Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One raises concerns associated with the future of humanity and of Hollywood. The film, whose main villain is an extraordinarily powerful artificial intelligence, was released to cinemas during the dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers, who in addition to fair compensation also demanded a guarantee that they would not be replaced by modern technologies. The computer-generated illusions in the film threaten the approach to truth and relativise the ethical categories of good and evil. Ethan Hunt/Tom Cruise is naturally the only safeguard against machines taking over the world, the last link holding human society together (this is literally true in the final action scene, when his partner uses him as a ladder). What awaits him is a confrontation with the most powerful adversary he has faced yet, which collects our best-hidden secrets, reshapes reality and is everywhere and nowhere. In other words, he will have to take on a (false) god, whose interests are represented by a villain with the biblical name of Gabriel, and the key to controlling it is in the shape of a cross. ___ Though few people in Hollywood today are able to so effectively evoke the dizzying feeling of forward motion as a running Tom Cruise, Dead Reckoning is to a significant extent a film of reversions, to the old faces and analogue technology of the Cold War period, to the protagonist’s past and to the skewed angles of De Palma’s paranoid first Mission: Impossible. And even deeper into the past. To The General, Hitchcock’s comedy spy thrillers and related 1970s caper comedies like What’s Up, Doc? McQuarrie combines the structural principles of the cinema of attractions and classic Hollywood, but he intensifies the situations and takes them to such an extreme that even the characters sometimes laugh resignedly over their impossibility. Tension arises between the (unseen) classic and (self-reflexive) post-modern approach to style and narrative when the film alternately fulfils and defies our expectations, as it is playfully ironic at times and tragically romantic at other time. Similarly to the way Hunt defies the algorithm and how the protagonists are aided by disguises and advanced surveillance technologies, which fail repeatedly, however. In the end, they can rely only on human bodies, ingenuity and teamwork. ___ The characters’ distrust and suspicion toward what they see and hear is expressed in the dialogue scenes by the tilted camera shooting from up close and in decentred compositions of the actors’ faces. Sometimes without establishing shots, which, together with the hasty editing (including cross-axis jumps), intensifies the feeling of disorientation and the impossibility of determining what is true and who is running the show. At other times, usually while the next course of action is being planned, the camera uneasily circles the characters. Thanks to this, even the chatty explanatory sequences are thrilling and there are practically no statics moment in the film. The almost cubist composition of the picture occurs roughly at the midpoint of the narrative during the meeting of most of the key players at a party at Doge’s Palace in Venice. The characters’ dialogue as they try to figure out their adversaries’ motivations is edited in the rhythm of the diegetic background music. Their verbal shootout is reminiscent of a dance performance, as every camera movement is synchronized with the soundtrack. Also in other scenes, though not as conspicuously, the information conveyed is of comparable importance as the aesthetic pleasure of the interplay of shapes and lines. For example, during the chase through the narrow and dark streets and canals of Venice, the order of shots is not determined only by the continuity of the ongoing action, but also by the rhythmic alternation of contrasting and complementary angles and movements. ___ The episodically structured film traditionally comprises several massive action sequences, each of which having its own objective, obstacles and course of development. At the same time, they are firmly interlinked. Each one prepares us for what will happen next (which doesn’t always go according to the presented plan) and sets in motion another notional cog in the flawlessly tuned mechanism. The chosen locations also complement each other, as they give the characters less and less room to manoeuvre (from an expansive multi-level airport to a closed train). Almost every sequence works with a tight deadline and the necessity of precise timing, both across the given sequence and in its constituent parts (for example, the necessity of escaping from the car before it gets destroyed by an oncoming metro train at the end of the Rome sequence). ___ Unlike in blockbuster comic book adaptations and the high-octane, progressively dumber Fast & Furious movies, the human element is never overshadowed by the shootouts and explosions in Dead Reckoning. On the contrary, they are doubly suspenseful thanks to the chemistry between the believable characters. Their characterisation, which is carried out without pauses in the action or during their preparations for the next task, is skilfully connected with certain recurring motifs and props (e.g. Hunt’s lighter, the passing around of which among the characters reflects the development of the relationship between Grace and the protagonist). That’s what the franchise is about, as Cruise doesn’t hesitate to risk his own life again and again with maniacal determination in order to convince us that an intelligent machine can never do anything as spectacular as a human (or a team of humans) can do. In the latest instalment of the M:I franchise, which is the most narratively harmonious and stylistically experimental of the lot, he does this for the first time not only in the subtext, but in the foreground. The time for subtlety has passed. 95%

On the Adamant (2023)

Like the participants in Philibert’s other documentaries, the visitors of the L’Adamant Day Centre in Paris try in many scenes to find the right words or other means of expression inspired by art therapy to convey their emotions and stories, or rather to establish contact with others. Through patient observation as well as through listening to and preserving conversations in their entirety, e.g. without deleting the moments when his subjects address the crew members, Philibert highlights the uniqueness of the individual participants’ manner of communication, their diction and their choice of expressions (some invent their own), and the gestures, facial expressions and tics that accompany them. Whereas in hierarchical social systems we try to fit into an artificially constructed role with which we have become familiar and to think and speak in a standardised way in the interest of preserving our status, on the Adamant – a somewhat utopian world with its own rhythm (corresponding to the fact that people are constantly coming and going and nothing is as permanent as the Seine, on which the floating daycare centre is located) – such games are not played. Or rather, when someone does play that game, it’s usually done consciously in the context of therapy. Role-playing and constructing a fiction that’s nicer than one’s own disordered reality is tellingly the topic of the films (8 1/2, Day for Night, Through the Olive Trees) selected for a festival that the social actors organise in one of the workshops and whose preparation is defined by the timeframe of the narrative. ___ The people on the Adamant aren’t concerned about how they appear to others or whether expectations are met. Everyone is in the same boat. Philibert’s new film can be seen as an argument for psychiatric care reform or generally for a more understanding approach to people afflicted with mental illness. For me, it is primarily a film – exceptionally powerful in its honest humanism and empathy – about the art of living together in spite of our differences and regardless of the fact that some people think and speak differently. On the Adamant is very deserving of the Golden Bear that it won. 85%

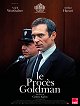

The Goldman Case (2023)

The Goldman Case is a masterclass in how to grippingly direct (and edit!) a courtroom drama that takes place almost entirely in a single room without needless embellishments (and, furthermore, is shot in the television format that corresponds to the time when the trial was held). In terms of acting and the screenplay, The Goldman Case is equal to Anatomy of a Fall, at whose centre stands a similarly complicated character and which raises similar questions (Doesn’t the one who can tell the more convincing story and give a better performance win in court? Do words have more weight than actions in the end?). And though it involves a case from the 1970s (a left-wing Jewish activist denies murder charges), in the second plane the film delivers an almost sociological overview of French society at the time, the clash between the right and the left that plays out in the courtroom, the inability to see a person outside of the box in which we have placed them based on their political orientation or background, and the unwillingness to see that some facts can be black and white at the same time, all of which is in some ways reminiscent of today’s culture wars. 85%

The Idol - Pop Tarts & Rat Tales (2023) (episode)

After the promising first shot, the quality only deteriorates. First there is an inept attempt at show-business satire, which in the context of the issues addressed here might have been relevant at the beginning of the millennium, with good-looking people dancing and smoking, then more dancing and smoking people in nicely lit shots, and finally a bit of similarly chaste eroticism that doesn’t cross any boundaries as in Fifty Shades of Grey (only the moaning is louder here). The dialogue has about as much in common with the actual speech of real people as chicken nuggets have with real meat. The rhythm is completely off and all of the actors (most notably the Weeknd) are all over the map with their speech, rarely ending up in the same place. It’s provocative only by how many levels on which it doesn’t work. The whole thing has a sort of embarrassed pubescent vibe, as if Sam Levinson wanted to shoot a porn flick but was afraid of what his parents/HBO would say, so he awkwardly fabricated the illusion that he is pursuing a purpose higher than mere (self-)gratification through his work.

The World According to My Dad (2023)

This film/discussion starter was obviously made in a primitive way, though with the tremendous passion and conviction with which it is necessary to undertake certain projects, however misguided they may outwardly appear to be. Simply because they can bring forth something good. For example, a climate that won’t kill us. The difficult effort to publicise Svoboda’s idea for a global carbon tax is intertwined with the buddy-movie story of a father and daughter (for whom the film is, among other things, a way to understand her dad). Thanks to this, the ending of the film is not entirely depressing, as it does a good job of showing how the protagonists’ relationship has been transformed during their mission together instead of highlighting failure. It also avoids being depressing thanks to the natural humour and the dynamic between the characters defined through, among other things, recurring situations (economical loading of the dishwasher) and endearingly goofy songs, which liven up the narrative whenever it seems that the wheels are about to come off. One of the few films about environmental sorrow that won’t leave you feeling dejected when it’s over. 75%