Directed by:

Alejandro González IñárrituCinematography:

Emmanuel LubezkiComposer:

Antonio SanchezCast:

Michael Keaton, Emma Stone, Zach Galifianakis, Naomi Watts, Jeremy Shamos, Andrea Riseborough, Damian Young, Natalie Gold, Merritt Wever, Edward Norton (more)VOD (2)

Plots(1)

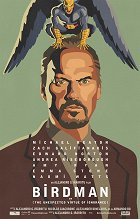

BIRDMAN or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance is a black comedy that tells the story of an actor (Michael Keaton) - famous for portraying an iconic superhero - as he struggles to mount a Broadway play. In the days leading up to opening night, he battles his ego and attempts to recover his family, his career, and himself. (Fox Searchlight Pictures US)

(more)Videos (13)

Reviews (21)

All the brooding, sadness, decline, or self-examination may not be too original at its core – but that infinitely perfect form is. After two breathless and witty hours, it is almost irrelevant that Alejandro González Iñárritu, as is his custom, once again goes too far and shows even what I don't really need to see or hear in order to understand or enjoy it. Michael Keaton and Emma Stone, however, pass and play solos with such captivating pacing that in the escalating scene of the final performance, I forgot to breathe.

()

What an amazing film experience! Birdman is a sad story about a broken man who longs for the recognition he will never receive. So, basically, your typical Iñarritú’s downer, but this time wrapped in a very refreshing and energetic format. We can debate about the ending, and I’m going to write my opinion on it (spoiler!), so if you haven’t watched the film yet, stop reading now! The entire film is about Riggan trying to gain recognition and long lost glory. He’s convinced that he has abilities that those around him don’t appreciate. He’s not so much after inner artistic expression, he simply wants his play to be successful. When he realises that an unlikeable and influential critic will bury his play at any cost, he attempts to “buy” its success with one last desperate idea: suicide on stage, but not a real suicide – that would simply kill him. With manifest and embarrassingly vulgar gestures he tries to give the aura of an artist who has put at stake his life for his work. Cheap attraction, action, people want to see blood, they are used to it from mainstream movies. The audience applauds, the critic leaves in disgust because Riggan did exactly what she was expecting, maybe even worse. And Riggan dies, because when someone puts a gun to their head and shoots, they usually die. This is followed by a montage (!) and the epilogue. Thus far, the film pretended to be shot in a single take, even if it jumps in time and space, or when we follow the real Riggan or his hallucination. Since the epilogue is separated by the montage, it should make some sense that what we are watching is something different than we’ve been watching so far. It can’t be an alive Riggan, nor can it be what an alive Riggan is imagining while doing something else. To me it’s just an image of how Riggan would have liked his suicide-as-manifesto to ideally work out: a) he doesn’t die: b) the stunned critic writes a positive review, even though she said she would never do it; c) people are interested in him again; d) his daughter acknowledges what he has within himself and his miraculous abilities (the final look upwards). (End of spoilers). So, as I say, quite a downer, but I’m sure other people can have a different opinion. And that’s what’s so great about it.

()

With my minority opinion, I will probably be as unpopular as the theatre critic in the film, who was peculiarly the only character who managed to express the problem with the main character and, inadvertently, with the film as a whole. Just as Riggan longs to be an actor while being merely a celebrity, Birdman wants to be art while being merely commercialism. If the film (like Riggan) had not pretended to be something that it’s not and had instead acknowledged what it really is, I believe it would have actually ranked among the year’s best films. It is held down by the weaknesses of Iñárritu's preceding filmography – forced metaphysical layers, banal moralising and sadistic enjoyment of the characters’ suffering. Unlike 21 Grams and Babel, however, Birdman thankfully is not devoid of humour. Though the lumbering dialogue is in most cases eventually cut off by an inappropriate gesture or remark (Mike’s heart-rending monologue on the roof, Riggan’s use of self-therapy toilet paper), the further development of the narrative gives the grand speeches meaning. Besides the fact that Birdman is populated with eccentric characters and exaggerated gestures of the actors, the film itself is a boldly grand gesture in terms of its form. Creating the illusion of an uninterrupted flow of shots smacks of the similar self-centeredness and extravagance that typify most of the characters, while at the same time serving to thematise the dichotomy between film and theatre (where there is also no editing) and between the worlds of reality and fiction. The problem with these oppositions is that the film denies them with its permanently exaggerated fictional world. Throughout the film, everyone behaves as if they were actors in a grand theatrical performance. They act theatrically, behave in a curt manner (especially the offensively one-dimensional female characters, who serve primarily to highlight the talents of the strong men) and constantly verbalise their inner thoughts out loud, and their precise entries into the scene at the exact moment when the actor we have been watching has nothing to say and needs to react to someone betray the stage-managed nature of the film. When everything looks like a play, it is impossible to determine where (in the context of the fictional world) lies the boundary beyond which begins the imaginary reality inhabited by real people with real emotions. I understand that the blurring of that dividing line is one of the central motifs of the film, but if the line is blurred from the beginning, the contrast doesn’t work and there can be no development along that line. I don’t deny that Birdman is a remarkable piece of work. Perhaps I will gladly watch it again so that I can fully appreciate the dramaturgical segmentation of the outwardly uninterrupted narrative, but if I want to see a film whose main subject and quality are the actors, I would rather re-watch Cassavetes’s honest and unaffected Opening Night. Three stars for emotion, five for technique. 75%

()

(less)

(more)

Watching Birdman was very hard for me. In fact, it took me about the first twenty minutes to even figure out what I was watching. After those twenty minutes, I still wasn’t quite sure what was reality and what was fiction, but at least I was beginning to notice the outrageously perfect camera that shot everything without me feeling any cuts in the scene. Some moments were absolutely divine, and it seemed to me as if some of the actors were having endless dialogues, in which I wondered how they were able to remember so many lines. And since I doubt they remembered them by heart, I bow down before their perfect improvisation abilities. Whatever else could be said about it, this film will show you that Michael Keaton, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Naomi Watts and Zach Galifianakis can act like gods. I perceive this film a bit as a celebration of acting, but it also contains a feel of a certain ignorance and contempt for Hollywood. Everyone seems spell-bound by some kind of an oracle who knows everyone and makes them appear on the screen to justify themselves. Thus we see Michael Keaton making fun of superheroes despite playing one. When Edward Norton appears on the stage, he immediately starts to give everyone orders. Zach Galifianakis is unusually serious here and Emma Stone has a few dialogues that will take your breath away. Birdman is an incredibly strange film. Distinctive, never boring during its two-hour running time and definitely worth remembering. It’s not for everyone, but whoever wants to give it their attention will undoubtedly enjoy this movie full of well-made shots. And will fall madly in love with at least a few of its actors.

()

Birdman has a Woody Allen-esque theme and environment conveyed by the unique optics of Lubezki’s long shots, but without Woody’s wit and detached perspective and with irritating jazz disharmony. An occasional good scene (Times Square in boxer shorts, waking up on the sidewalk), some occasional good dialogue (Emma Stone and Edward Norton on the roof) and always great actors. But for an uplifting “artistic” experience, this portrait of a mid-life crisis and creative burnout is not enough for me.

()

Ads