Reviews (863)

Big Fish (2003)

Magical anti-realism in its most touching form.

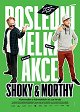

Shoky & Morthy: Last Big Thing (2021)

Andy Fehu’s new project is likable because, among other things, it doesn’t try to ply the same waters as his breakthrough revelation The Greedy Tiffany, although this may cause some mild disenchantment and unfulfilled expectations among viewers who were enthusiastic about his debut. On the one hand, the project has a whiff of Štěpán Kopřiva and his meta-reflexive work for experts in the area of genres and pop culture. Fortunately, however, Andy Fehu does not base his film only on quoting from particular models. He works with a more general and more generally applicable range of formalistic and stylistic associations, which he uses to enrich his biting comedy from the world of the young and self-absorbed. The awkward but sincere forty-year-old Radomil inevitably comes across as the most likable character. Tomáš Magnusek deserves considerable credit for this due to his breathtaking performance. This is where we see the difference between Shoky & Morthy and Kopřiva’s works with their casting of Michal David and Dada Patrasová. Fehu isn’t satisfied with a mocking wink and a role that benefits solely from the actor’s status as a celebrity. Instead, he gives Magnusek room to play the part with grace and a range that surpasses everyone else involved. If he doesn’t come away from this with a nomination for the Czech Lion for Best Supporting Actor or the Czech Film Critics' Award for Discovery of the Year, it will be a disgrace for both institutions.

Annette (2021)

Annette can be described as Carax’s Southland Tales, as it also raises great expectations that it doesn’t live up to, while presenting a distinctive and tenaciously conceptual vision that is both easy to brush off and fulfilling to interpret, and it also goes stubbornly against the grain, seeming obstinately serious while offering an inwardly atypical and subversive spectacle that, however, exposes and adores all spectacles in equal measure. If we look for parallels to Annette and delve deeper into Carax’s cinephilia, we may also arrive at Jacques Demy and his ultra-kitschy and, at the same time, subtly self-reflective and totally self-assured musicals, which looked misguided next to the New Wave of the time, though they were essentially New Wave due to their obstinate formality and artificiality. Similarly, Carax’s treatment of the screenplay by Sparks tells a story that is banal at its core; in this case, a tabloid romance from the world of show business, full of grand emotions. He presents it to us gnawed down not only to the marrow, but also to its essential theatricality, self-centred pomposity and performativity. If in Holy Motors he showed film as a medium of deception and illusion, even as he simultaneously sang their praises and elevated the nude king himself to an enchanting phoenix, in Annette he constantly presents the artificiality, unreality and lifelessness of his opera from the world of alt-pop music videos. Films that don’t give us what we want are actually in some ways the most honest and unexpectedly fascinating.

The Translators (2019)

The Translators perhaps wanted to be The Usual Suspects of the world of literary translation (which in and of itself is more than absurd), but with its overwrought twists, phantasmagorical depiction of the translation profession and its fierce seriousness and futile attempt at profundity, it overshoots far into the realm of WTF. Unfortunately, the film’s general sense of self-importance also makes it impossible to even laugh at it much.

Kings of Cult (2015)

It’s just two cameras and two old men having a talk, but since it’s Charles Band and Roger Corman talking about the changes in independent genre production from the 1960s to the present, Kings of Cult is a great source of information for people who are interested in this area of cinema. Their insight into the functioning of VoD versus VHS is especially beneficial.

Highway to Hell (1991)

Highway to Hell threads the needle between Albert Pyun’s scenographically imposing trash (Radioactive Dreams, Cyborg, Alien from L.A.) and Gregory Widen’s weirdly mythological genre flicks (Highlander, Prophecy), while remaining proudly in the realm of VHS trash. Besides a tremendous number of genre-pure flicks, the golden era of video rental shops gave rise to an odd subset of incomprehensibly bizarre films that brought to mind the genre equivalent of a Rube Goldberg machine. With zero judgment but grandiose creativity, they blended genre elements with flashy sets, and episodic narratives served as a field of unrestrained goofing off for the artisans in the costume and set design departments. We can find the portents of this trend as far back as the mid-1980s in isolated works such as the aforementioned low-budget Radioactive Dreams and the studio-financed Streets of Fire. But they absolutely blew up with likably overwrought movies like Cherry 2000, Rising Storm (1990), Mindwarp (1992), Split Second (1992) and Richard Stanley’s films. All of these flicks are united by the principle of belching out fragmentary elements using the scattershot method, where the resulting work only rarely holds together, firing various genre and formalistic attractions at viewers instead of relying on sophistication. At that time, precisely these kinds of films were highlighted by enthusiast magazines such as Fangoria, whose passionate writers and readers, who’d had enough of worn-out genre clichés, latched onto either explicit extremes or movies with the promise of an original take on genre elements and at least a basic amount of video-rental teen attractions with special effects and action sequences at the fore. Highway to Hell mixes elements of the Persephone myth with the aesthetics of westerns, rockabilly, horror and biker exploitation. Set in the desert and with the help of painted optical effects, the film’s version of hell takes the form of a masquerade ball, where phenomena such as the protagonist’s dog provocatively urinating in front of stop-motion Kerber and Gilbert Gottfried’s Hitler chatting with Ben Stiller’s Attila, the Scourge of God do not in any way stand out from the general coke-fuelled randomness.

A Quiet Place Part II (2020)

It is an unavoidable fact that A Quiet Place Part II cannot step into the same river as its phenomenal predecessor. The filmmakers are very well aware of this and thus don’t even try. In terms of plot, the sequel proceeds from what the first film established and then builds on it. The first one worked brilliantly with limited space, inventively imagined the world and its laws and, mainly, worked with sound as a means of expression, drama, storytelling and dramaturgy. Though it still adheres to the basic concept of the series, Part II uses sound to build tension within individual scenes, but the role of the central formalistic medium from which the film’s dramaturgy and narrative are derived is taken over by editing. Throughout the second half of the film, Krasinski maintains the suspense almost exclusively through parallel montages, but he also uses editing to gradually open up the post-apocalyptic world. The editing and, in a broader sense, the composition of the film and what it shows the audience, what it leaves out and what it leaves to the imagination, shows Krasinski to be not only a filmmaker with exquisite command of his craft, but also a creator capable of thinking in cinematic form. This ability elevates his films above the classic genre standard and places them alongside the best horror movies of the new millennium. Most other prominent genre filmmakers, such as Ari Aster, Robert Eggers and Jordan Peele, base their distinctiveness on visual stylisation and the strength of the screenplay. With Krasinski, we see a unique symbiosis of original high concept and the use of essential filmmaking techniques to achieve the maximum effect. Krasinski’s method of ratcheting up the tension reaches its full potential only in the cinema – with surround sound, a big screen and ambient darkness in which 130 people hold their breath all at once – and the sequel also proves to be an exceptionally effective machine for physically intense sensations (though it lacks the wow effect and spatial and conceptual density of the first film). This makes one even more aware of how modestly the filmmakers actually work with scares and, conversely, rely primarily on carefully prepared and escalating situations derived from well-thought-out Hitchcockian construction of the narrative and set design. Though I am generally not a fan of sequels, because they rarely offer anything original, in the case of the A Quiet Place series, I actually hope that a third instalment will be made. I want to see how Krasinski will pick up the gauntlet that he himself has thrown down and what cinematic means of expression he will choose as his weapon of choice.

The Legend of Baron To'a (2020)

The Legend of Baran To’a is an outstanding crowd-pleaser that plays by the tried-and-true rules of movies about outsiders and self-improvement narratives, but it brings a lot of needed modern updates to them. Besides the likable ensemble cast and inconspicuously inventive screenplay, however, the most surprising aspect of the film is the flawless choreography of the wrestling bouts. In accordance with the film’s concept, these bouts are dramatically intertwined with the narrative, develop the characters, don’t draw attention to themselves as a superficial attraction and adhere to the film’s overarching exaggeration and humour, despite their superb physicality. In fact, it can be considered a minor miracle that this entertaining treatise on roots, community and the personal quest to appreciate them manages to not only thrill audiences with its humour and characters, but also delivers some of the best planned and superbly filmed bouts of recent years in global cinema. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if Hollywood has already reached out to Kiel McNaughton, because he is shaping up to be another New Zealand pop-genre talent like Taika Waititi and, in his time, Geoff Murphy.

Red Hot Chili Peppers - Dark Necessities (2016) (music video)

In this music video, Olivia Wilde seems to reference Jonas Åkerlund’s visual style with its bold interiors and sharply lighted, fatigued bodies (e.g. in the videos for Robbie Williams’s “Come Undone” and Roxette’s “Wish I Could Fly”), which she supplements with a likable girl-power motif with female skateboarders portrayed by stuntwomen.

Wake Up (2020)

I spent the whole time wondering why something so well shot and acted was so intellectually one-dimensional and naïve, until it turned out that it wasn’t an original short, but a plain and simple PR spot by means of which an electronics manufacturer attempts to give the impression that it cares not only about customers, but also people generally. Margaret Qualley doesn’t go all out this time in comparison with her other expressive-dance collaboration with Olivia Wilde, “Love Me Like You Hate Me”, and Jonez’s famous Kenzo World commercial.