Reviews (862)

Gunda (2020)

Gunda is very good at evoking all kinds of superlatives, such as in the official annotation and humorous slogans like “Babe in the style of Béla Tarr" and "behind the scenes of Wedding Trough”. This derives from its greatest virtue, but it has less to do with what the film is about than with its concept and treatment. In fact, in the context of modern cinema, it may seem like a revelation, as we are more likely to find parallels in the formats of YouTube and modern television. The ambient sound component gives the impression of ASMR videos and the action on the screen is reminiscent of slow TV, but with a more obvious dramaturgical and screenwriting element, which brings to the fore the themes of ecology, organic farms and, inevitably, the ambiguous relationship of civilisation and humanity to livestock farming and the ethics thereof. At the same time, however, it leaves a lot of room for viewers’ thoughts, which, like the animals on the screen, are given a relatively free range. Undisturbed by music, hectic editing and traditional milking of emotions or meanings, but concurrently stimulated by the moving and magnificently shot wallpaper on the screen, the mind begins to plant stories where there possibly aren’t any and to wander off in bizarre directions. The oft-mentioned screen is crucial in this, as it is only in the semi-darkness and with the relinquishing of control over the film provided to us by remote controls and keyboards that the desired calming of the senses can occur, enabling not only contemplation but also simply a relaxing release of the mind’s reins.

Arena (1989)

Arena is one of the titles created during the collapse of Empire Pictures and was subsequently taken over and released by other companies following Empire’s liquidation. Together with the earlier Zoone Troopers, it represents the materialised soul of Charles Band’s trash factory. Whereas other production companies on the mid- and low-budget spectrum targeting the international video market at that time usually specialised in a particular genre, as was the case of Cannon Films with action movies and New Line Cinema with horror flicks, Band’s projects straddled all possible styles and genres, though they were united by fantastical motifs and, above all, special effects. Arena is simply a boxing flick with a gangster twist, which means that it takes place in a cardboard sci-fi setting and the main protagonist fights with rubber monsters. And it works splendidly thanks to the setting and costumes cut out (with a wink) from the cloth of Star Trek, which don't refute the film’s grand ambitions and the limits of its budget and give the prescriptively schematic narrative borne on the shoulders of a futile ensemble cast not only the necessary uniqueness, but mainly a delightfully cheap charm.

Dragonslayer (1981)

Though Dragonslayer was unfairly overshadowed in its time by more spectacular and bombastic blockbusters, it is not only one of the essential titles of the Walt Disney Studios’ Dark Age, but also one of the most original fantasy movies of all time. The fantasy movies of the 1980s and, for that matter, of more recent times essentially used either Tolkienesque quest motifs or heroic Conan-style action narratives, but both forms simultaneously are built on exploring fantastical worlds with spectacular special effects and costumes. As opposed to that, the screenwriting duo of Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins came up with the concept of magic and dragons set not in opulently spectacular mythical worlds, but in the Middle Ages with its caste system, bleakness and earthiness. On the other hand, they also wanted to avoid the stereotypical griminess and degradation associated with that era, or rather with its cinematic image. Under Robbins’s directorial guidance and thanks to generous production in a unique co-production of Walt Disney Studios and Paramount (the second project resulting from this collaboration was the similarly inconspicuously iconoclastic and creatively distinctive Popeye directed by Robert Altman), a realistic world was created that exudes extraordinary life in its intimacy and insularity. The film and its setting come across as inconspicuous, but thanks to the precision of the mise-en-scene and locations, it seems realistic without ever standing out and drawing attention only to itself. The most surprising thing, however, is the way Dragonslayer works with the motif of magic, which is constantly doubted, related to ordinary people and seized by representatives of the Church and the ruling authorities for the purposes of power. This storyline reaches a surprising climax in an unexpectedly bitter conclusion, which sets forth the fatal paradox of the dragon-slayer character, i.e. the slayer of creatures and of forces transcending the human world. Together with The Black Hole, The Watcher in the Woods, Tron, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Return to Oz, Dragonslayer forms the backbone and absolute peak of Disney’s dark period and, like those other films, it is distinguished by inspired originality, unexpected complexity and stimulating ambiguity. Whereas in the first half of the 1980s other studios were churning out blockbusters and building up franchises, which dominate pop culture to this day, Disney was following a path of quality, originality, progressiveness, non-conformity and creative ambition. It’s no wonder that viewers rather flocked to the competition from Lucasfilm and Amblin, which were superficially more entertaining. Conversely, the mid-budget Disney films of the time wagered on civility (the coming-of-age drama Tex), commitment (Night Crossing, about an escape from East Germany) and meta-genre aspects (Condorman, Trenchcoat). The aforementioned backbone titles represent the unique phenomenon of anti-blockbusters that elicit amazement in equal measure through their audio-visual spectacle and themes, and furthermore prove to be far more mature and deep-thinking than those sophisticatedly crafted but essentially trashy blockbusters. However, history, or rather those who write it, decided to emphasise performance and ease of digestion instead of the aforementioned virtues, and thus that period is now considered to have been neglected and actively marginalised within the corporate narrative of the Disney brand (most of the aforementioned titles are not widely available) because it doesn’t fit in with the strenuously constructed image of a playful family-entertainment factory.

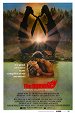

The Burning (1981)

Carol Clover shed a lot of tears over The Burning. The influential film theorist came up with the now widely used concept of the final girl and established the slasher as a subgenre that positively lends itself to the feminist viewpoint. Subsequent studies, such as Richard Nowell’s work, demonstrate that slasher producers, in response to the market of the time, also absolutely counted on a female audience and thus deliberately populated the genre with active female protagonists and constituent motifs that resonated with the female part of the audience. Opposed to this contemporary context, The Burning presents a fetishistically violent and fiercely misogynistic counterpoint. As such, the film defies causality and internal logic, but it is held together by its disdain for and objectification of women. The girls at the co-ed summer camp are viewed through a voyeur’s lens and emerge from their individual situations primarily as whores who make a lot of fuss and all they think about is sex. The central killer is supposed to be driven by a desire for revenge for the horrific burns inflicted on him by a group of privileged boys, which he satisfies by mainly killing the girls rather than dispatching the macho bullies at the camp. Could all of this somehow be related to the fact that this flick was written and produced by Harvey Weinstein?

The Slayer (1982)

The Slayer is an excellent slow-burn horror movie with a brilliantly constructed atmosphere and carefully drawn-out suspense.

Pumpkinhead (1988)

Pumpkinhead works as an opulent demo for Stan Winston and his costumes and special effects, as well as for the cinematography, lighting and set-design departments – in all of these aspects, Pumpkinhead is maximally effective. The visuals, superbly supported by colour filters, are actually revolutionary for their time, anticipating by a few years the trend of pastel colours popularised in the early 1990s by the music videos of David Fincher and Michael Bay and the feature film Kalifornia, on which Bojan Bazelli was also in charge of the cinematography, as he was on Pumpkinhead. It’s a pity that the screenplay isn’t nearly as well developed as the visual aspect of the film and makes do with an extended, run-of-the-mill fairy tale. Film connoisseurs will enjoy the film as one of Lance Henriksen’s few starring roles, despite the fact that he doesn’t exactly get much space here, as he plays second fiddle to the effects, costumes and sets.

Godzilla vs. Kong (2021)

Whereas Disney had to put Winnie the Pooh in the vault in order not to irritate the great Xi Jinping, Warner Brothers found a way to not only milk one of its main bits of IP, but also to please China mightily. Kong and Godzilla thus head to Hong Kong to measure their strengths against each other. On the one hand, that means a lot of visually rewarding neon, but, mainly, this time it involves more than just the monsters slightly dishevelling some iconic landmark, as was previously the case. Rather, they literally raze the whole problematic and rebellious Hong Kong to the ground. With, of course, the exception of the Bank of China Tower, which is the dominant feature of their night-time battle, but the monsters don’t dare even to touch it – although this iconic building absolutely asked for some sort of interaction, the filmmakers used their potential on the Central Government Complex and Hopewell Centre. The studio tries to flatter the domestic audience of post-Trump America by nodding to the supposed populist subversives of the Illuminati conspiracies and canonising alternative facts around the Hollow Earth theory in order to ingratiate both groups of their contradictory interpreters (according to some, there is a habitable cavity inside the Earth, while others, based on the example of Kong’s habitat, claim that we live in the cavity and the view of the sky is an illusion). But perhaps it’s actually a well-thought-out and coherent dramaturgical concept that at the moment when the monsters aren’t beating the shit out of each other, the rest of the film is completely out of hand. As with the previous instalments of the new international kaiju franchise, I see parallels with the old films, but that doesn’t make the new one any smarter or more satisfying for viewers. Godzilla movies always somehow reflected the phenomena and social issues of the time in order to be relevant to their viewers, but at the same time, it was all much more entertaining and guileless back then. Today, clearly in parallel with our own time, everything is frantically elaborate, overloaded with absolutely useless information and über-complicated lore. Why don’t they just simply make a monster flick instead of all of those idiotic scenes with human characters who watch the kaiju even when they’re not fighting. I'd rather watch Godzilla just swimming, sleeping or knitting a pair of socks than any of those moronic scenes with human characters. But perhaps we have to be worthy of those scenes with the titans and, when it comes down to it, the fact is that it’s really worth it.

Operation Warzone (1988)

The Vietnam War is a frequent motif in the work of crazy military fan David A. Prior, or rather it was in the initial phase of his career, when before he had familiar faces in front of the camera and real semi-professional production, he was filming with his friends playing army in the woods at the edge of town. It is essential to look at how he works with this motif in order to understand Prior and his form of militarism. In his whole filmography, only one movie, Operation Warzone, officially takes place in Vietnam. Judging by the descriptions put on the VHS cassettes, some foreign distributors also placed Hell on the Battleground in Vietnam, but that went against the master’s intention. Being an unsuccessful war, Vietnam would not fit well with Prior’s childishly boisterous movies, but would rather leave an unpleasant aftertaste. Prior generally uses Vietnam as a trauma that the heroes must overcome, achieving victory in the process (Killzone, Night Wars), or an essentially unresolved past from which they have taken training and attitudes that they subsequently apply to another conflict (Deadly Prey, Jungle Assault). When Prior presents his vision of wartime heroism in Hell on the Battleground, he characteristically does so in a fictional conflict so that the stigma of impending defeat doesn’t hang over the heroes’ heads. Therefore, Prior’s only real excursion into the Vietnam War takes the form of a completely surreal and wildly absurd farce that is deliberately divorced from reality. In the same way that boys playing soldiers dream up their own variations of wars based on not wanting to be on the losing side, Prior serves up the ultimate ’Nam fantasy. The hell with Rambo, who only brings home a few POWs after the war has been lost. Prior’s tough guys in green not only enjoy all of the iconic attributes like clambering through tunnels, mowing down Viet Cong and rescuing prisoners, but they even reverse the course of the entire war and ensure an American victory. Because, as every military enthusiast knows, the outcome of the war in Vietnam was decided only by opportunistic bureaucrats and lobbyists in Washington, whose machinations and interests prevented the invincible American infantry from winning. What is most breathtaking about Operation Warzone, however, is how little it takes itself seriously. There is no sign of the bombastic pathos of Hell on the Battleground; rather, everything has the almost light-hearted feel of a weekend excursion. This is largely due to the completely subversive synth music, which in many scenes evokes the background music of family TV series (and particular motifs are very reminiscent of the theme song of the British series Dempsey and Makepeace). The narrative itself does not rely on the classic formulas of war films at all, but instead draws inspiration from adventure movies set against the backdrop of war, such Kelly’s Heroes or even Zone Troopers. The elaborate plot establishes an insipid McGuffin, which then enables the constant piling on of absurd twists. Mainly, however, it allows a completely unbridled adventure in which someone is always running somewhere or shooting at somebody. While we’re on the subject of running, the whole film is very frantic. Prior evidently got a Steadicam to play with, so there’s an atypical number of moving shots. When it comes to the maestro’s hopelessly stiff firefights, which merely alternate between counter-shots of people standing around shooting at each other without being able to actually hit anybody, he constantly has someone running in front of the camera or behind the characters to get the effect of a bigger production. The flick’s overall goofiness is significantly increased by the manic overacting of David Marriott, who, for some unknown reason, thinks he’s a master of accents (so here he plays an Australian, whereas he was a Scot in Jungle Assault). Wonderful details like the fact that the film’s entire cast is composed of overweight white thirty-somethings and that the Vietcong wear only grey shirts and chinos (with loafers and white socks), but no helmets, because there was no room for them in the budget, only add to the overall magnificent impression that one gets from the film. Simply no one can make war as much fun as David A. Prior.

T-34 (2018)

Valorous bukkake of heroism, pathos and gluttonously staged tank action. A juvenile war fantasy combined with fetishistic adoration of the T-34, thus creating one of the most bombastic and entertainingly boorish movies of all time. Formalistically, it’s like Michael Bay with a vodka drip inserted straight into his heart and, conceptually, it resembles David A. Prior’s most puerile work. Whereas American cinematic propaganda has always aimed for the heart, taking pride in emotions and story, thanks to which it is enticing and misleading, the Russians overwhelm and conquer viewers with hysteria and deafening spectacle. If classics like The Fall of Berlin are sledgehammers that pound the desired ideals and values into people’s heads at a slow manual pace, then T-34 is an out-of-control, nitro-powered jackhammer (it’s no coincidence that Sidorov previously made boxing flicks). The hell with American blockbusters; I haven't had my head beaten in to such a degree since the first time I saw Commando when I was a kid. I hope there’s a sequel and a T-34 vs. Godzilla vs. Kong crossover coming soon.

Ghoulies III: Ghoulies Go to College (1991)

Whereas the other brands that Charles Band spewed out into the world during the Empire Pictures era were openly and unofficially further developed following the bankruptcy of his legendary company (specifically Trancers and Robot Jox), Ghoulies set out on a journey through the leading trash production companies of the VHS era. With each instalment, the franchise got a different form that reflected and further developed, but also negated, the preceding canon. Paradoxically, this also leads to the fact that the parts of the series have more or less has similar average ratings, but instead of a universal consensus as in the case of most other series, we rather see conflicting preferences of fans. Some prefer the first instalment with its emphasis on witchcraft and visual effects, while others like the second one with its obvious attempt to create a caustically funny and bloody variation on Gremlins. After the collapse of Empire Pictures, the series was picked up by Vestron Pictures, or rather its primarily video-oriented division Lightning Pictures. In the interest of continuity, directing was entrusted to the resident special-effects whizz John Buechler, but at the same time, the third Ghoulies was pushed significantly in the direction of the more universally accessible teen comedies of the day. In the interest of overall stylisation, the demonic imps speak for the first time and when it comes to certain exterminations, they have an admittedly comic-book, almost slapstick stylisation. Combining the malevolent and mischievous imps with frat-house humour and the adolescent shallowness of Canadian jokes helps this bizarre but unsurprising mix to overcome its own limitations and extract maximum entertainment out of the functional symbiosis – i.e. it’s still within the boundaries of juvenile humour that adores lousy acting, cheap beer and boastful privileged exuberance. Its grim and egocentric essence is unintentionally made more obvious by the fact that the main protagonist looks like a young Donald Trump.